By Bernard Zuel

“Performers should not be scared of playing complex and good music,” the acclaimed Scottish guitarist Sean Shibe once said. “And listeners should try not to be scared of listening to it.”

“Oh no, no no,” Shibe says now with horror, mixed with a small sliver of humour, when I read it out. “You are quoting 19-year-old me. That’s terrible.” To be fair, he has a point. Not everyone wants to be held to what they said when they were barely out of school, not least because a good many of us would struggle to remember anything we said then.

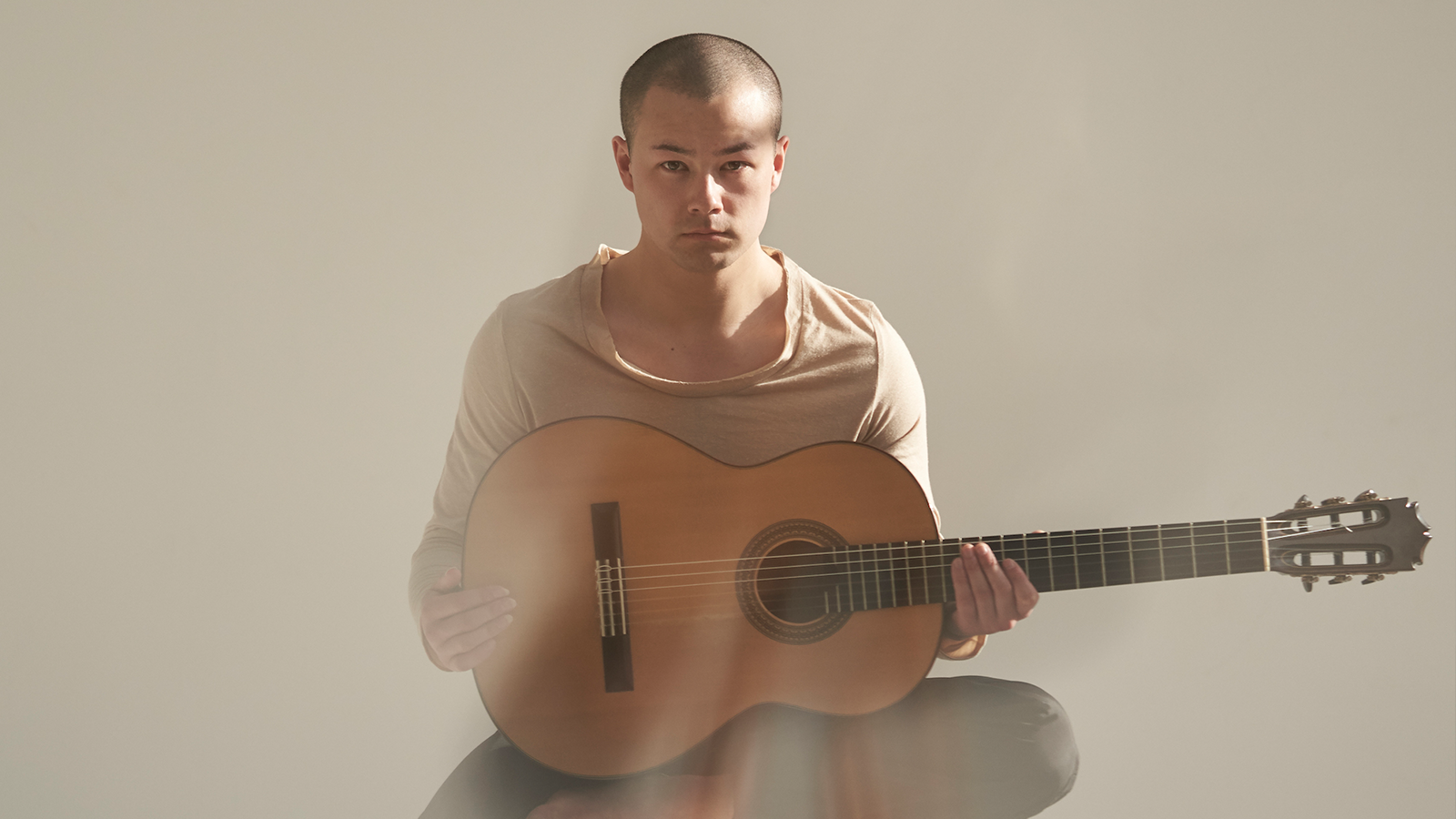

Shibe (pronounced she-beh) has always been happy to play outside the norm. As Australian Chamber Orchestra audiences will see on his first Australian tour, he’s a guitarist who is comfortable incorporating electric guitar into classical repertoire, whether he’s playing baroque or transcriptions from centuries-old Scottish manuscripts.

In his classical career, he’s been a pioneer. He was the first guitarist selected for BBC3’s prestigious New Generation Artists scheme, the first to be awarded a Borletti-Buitoni Trust Fellowship and to receive the Royal Philharmonic Society Award for Young Artists. His awards include two Gramophone Awards and the Leonard Bernstein award.

If the instrumental variety and adventure he possesses is at one end of the program he will perform with the ACO, at the other is the equally complex and sometimes fraught issue of cultural roots. The immigrant experience of being from a place but yet not entirely of that place is very familiar to Shibe.

His mother is from a small fishing village in Japan and his father was from London. They met in Edinburgh, where Shibe grew up. One of the peculiarities of his childhood was being regularly asked “where are you really from?”, with the answer – “from right here” – never being quite enough.

Growing up, he felt a degree of alienation, and as a young adult he wasn’t sure whether he felt particularly Scottish. But this has now changed.

“I feel pretty Scottish,” he says firmly. “It’s also a political thing: when I look at the movements in the UK that are shifting things [such as Brexit] and Scotland has been more resistant, it does increase a sense of specific identity. I think also gradually growing a sort of presence in this country has been healthy. I think when I was growing up in the ’90s in Edinburgh it was a very ethnically homogenous place and that had an effect. It definitely was not the most racist place and we’ve moved on in some ways as well, but I think those early experiences were quite formative.

“I do feel Scottish. I feel probably more Scottish than European. I definitely feel more Scottish than British, but I think a lot of Scots would say that.”

“I feel pretty Scottish,” he says firmly. “It’s also a political thing: when I look at the movements in the UK that are shifting things [such as Brexit] and Scotland has been more resistant, it does increase a sense of specific identity.”

His mother encouraged Shibe to learn guitar, which he took up initially with a “yeah, sure, why not?” attitude. Early on in his studies, he rejected the growing trend of developing multifaceted artists who are comfortable in cross-genre collaborations. Was that the purity of the convert or the certainty of youth?

“When I was going through the conservatory, the gift that they give you is the time to explore really how deeply you can go with the repertoire,” he says. “At that point it was really important for me to be able to understand how focused you could be on something extremely specific. I don’t think I felt able to think about branching out until I sort of dealt with that. I think it was neither uncompromising youthful attitude nor the zealotry of the convert – it was more a structural or timing decision.”

The electric guitar is a very different instrument to the classical acoustic instrument, with more to learn, he says. “There are some composers who would be interested in writing for classical [guitar] but they feel like the electric guitar really does speak to them. … It’s more than an instrument, right? It’s like a conceptual broadening which has been totally liberating.”

“When I was picking up the electric guitar for the first time, there was a lot of flak that I got from colleagues and friends as well who felt like it was a bit showboating or posturing,” he says. “In some ways I think that didn’t surprise me at all, and to me, summed up the lack of open-mindedness that the guitar, the classical guitar, can suffer from these slightly siloed positions.”

Technical knowledge is only one part of what he describes as a different way of thinking when approaching his instrument. “You are using ideas of colour to communicate a larger-than-reality sense of volume and projection and sustain. You’re actually able to add on these things that do create it in a very objective way,” he says. “But it’s not a vehicle of conservatism. It’s something that is constantly being updated, whereas the acoustic instrument that I’m playing is a copy of a 1930s instrument which is a copy of an 1890s instrument. It’s quite conservative guitar-playing and classical guitar is quite the conservative enclave, but the electric guitar is constantly developing, constantly reiterating, and the technology is really incredible.”

What then does the traditional music of Scotland mean to him now? Another exotic music to find a path through, or something closer?

“It’s the soundtrack to my upbringing and I think of different ideas of home when I hear it,” Shibe says. “I spent a lot of time at Gaelic festivals when I was younger, with folk musicians, and there was a lunchtime ceilidh band rehearsal at school. It’s part of the climate here, as normal as the autumnal cold.”

When music of place becomes so ubiquitous, it can lose a sense of specialness. Was there a time when he started to see it as more than just the music of the place, and instead as music that belonged to him?

“Yes, but also the fact that it is of a place is what makes it so powerful as well,” he says. “For me that is a strength: it is evocative and distinct [and] my relationship with Scottish music is always expanding into different areas that I hadn’t anticipated. So I spend a lot more time with Scottish musicians than I used to. I’ve got a collaboration I’m putting together with [composer/folk music fiddle player] Aidan O’Rourke in December after I get back from Australia and it’s been really rejuvenating.

“In Scotland, in these manuscripts that hold Scottish sources, Scottish versions of Dowland’s ‛Lachrimae’ for instance, there were also folk tunes. It was really that recently, in the 1800s even, that we did not make these distinctions [between] folk music and ‘higher’ music. It was really seen as pretty one and the same. And when you come into contact with the lute manuscripts that is crystal clear.”

The idea that traditional airs are played in the parlour rather than the concert hall lasted for a while in certain quarters, he says. “A lot of the sources in the lute books, a lot of the time this music was played privately and there wasn’t an audience in the way that we think about it: it was still essentially salon music.”

Does this traditional music bring vitality, discovery and freshness for Shibe, rather than the fustiness some see in tradition? “I don’t see the traditional necessarily as fusty,” he says. “It depends how it’s treated. We can’t help but treat these pieces as contemporary things – that’s what we are always doing as performers, contextualising them.”

“Yes, but also the fact that it is of a place is what makes it so powerful as well,” he says. “For me that is a strength: it is evocative and distinct [and] my relationship with Scottish music is always expanding into different areas that I hadn’t anticipated.”

One of the contemporary pieces in the program, Julia Wolfe’s Lad – written originally for nine bagpipes – is an American take on Scotland, while James MacMillan’s “From Galloway” brings an English perspective; both are reflections from outsiders. Lad is anything but gentle guitar music: it feels imposing, it cuts through and is a demanding piece because of its forcefulness. This has clear appeal for some, maybe generationally, though that same thing can trouble.

“I think all of these pieces are just good pieces,” says Shibe. “I think that [Lad] says something about the strength of the diaspora. It says something about the spirit of the pipes. It is also piece that as a guitarist is so seductive because it has a forcefulness that the guitar is rarely able to muster.

“I feel like some of my favourite performances have been when you’re on the stage but you can feel it vibrating. It’s a thrilling experience if the audience are in the state for it.”

Much the same could be said of the work of Martyn Bennett, a Canadian-Scottish composer who, until his early death at 33, melded Celtic traditions and contemporary formal music with an electronic base. But Shibe is drawn to Bennett by more than a shared expansive view of what music can be.

“That fusion of tapes from the ‘50s of Wee Free preachers and beats and bagpipes is just as heady as it was then. And actually, just as unique. Nobody has really done it with the same vigour since.”

“I went to the same school as Martyn did, albeit he wasn’t there when I was there, and his presence was really deeply felt. We would play his compositions in the orchestra, as cellists,” Shibe recalls. “For example, for the opening of the Scottish Parliament in 1999, one of his pieces, Mackay’s Memoirs, was played. I remember when we recorded that in a studio in Glasgow [in 2005], it was just after he passed away, it was a very powerful experience.

“As I got older I got more interested in what he was doing musically with those albums like Grit and Bothy Culture and I recognised that what he was moving towards was more what we think of as traditional classical composition. So that was interesting that he was moving through all these different phases relatively seamlessly.”

Describing Bennett as “an EDM [electronic dance music] artist who was way ahead of his time”, Shibe concedes some of the musical innovations may sound a bit dated now but “that fusion of tapes from the ’50s of Wee Free preachers and beats and bagpipes is just as heady as it was then. And actually, just as unique. Nobody has really done it with the same vigour since.”

If there is an element of the time-stamped about some of Bennett’s work, it’s probably because we can forget how startling it must have been at the beginning. And there is still a thrill in the way Bennett brings these elements together, viscerally and intellectually, being of Scotland and beyond, both challenging and inviting.

As Shibe said when he was only 19, no one should be afraid of complex music.

Written by Bernard Zuel

Bernard Zuel is a Sydney-based arts writer, specialising in music, and a lecturer in journalism at Sydney University. He worked for The Sydney Morning Herald and The Age for 25 years and was the SMH’s senior music writer and critic. As well as a founding, and continuing, judge of the Australian Music Prize, co-host of the online music program, The Right Note, and host of a podcast on music pioneer, Harry Vanda, he is a frequent contributor on television and radio.

Scotland Unbound is touring nationally to Wollongong, Sydney, Brisbane, Canberra, Melbourne, Adelaide and Perth, 7-20 November. Click here to buy tickets.