By Stan Grant

God in Nature

In the darkness just before the break of dawn I see God in a moonbeam. I hear a splash and peer over the bridge and there, illuminated, is the unmistakable form of a platypus. The old people here had told me about a family of these shy, strange mammals living in the creek that runs alongside my house in a small village in New South Wales’s Snowy Valley. On my morning and evening walks I searched for them, but they were elusive. Perhaps I was looking too hard, like a pilgrim trying to find God when it is God who must find me. Now – when I am not expecting it, lost in my thoughts – she appears.

I watch her now as she swims in the stream – dancing almost – in the streak of silver that lights up the water. There in the cold dark before dawn, I think that this is what it must be to see God: this is Eden, where God walks in the garden.

This is my father’s Wiradjuri country – a place of beauty and pain, invaded but unconquered and alive still for us all. My father says what is most important is not who we are, but where we are. Dad is an old, wise, scarred man nearing the end of his life. He has battled his demons and put down his armour. His soul is at peace and the earth – his Country – gently holds him. From him, I have learned that everything – all of creation – is the image of God. From the moment of the birth of the universe, all the possibilities of our world spring forth.

The platypus knows nothing of the Fall. She does no harm, raises no armies, profits no fortune. What is God? Saint Augustine said if we think we know God then we do not know God. Saint Thomas Aquinas called God “Ipsum Esse” – the act of existence. Yes. That’s it. The impossible possibility. The known unknown. The

creation ex nihilo – from nothing, comes something. Creation is an act of love and we know God by our capacity for love.

This morning I see God in a moonbeam. And all is beautiful in my world.

All shall be well and all shall be well

And every kind of thing shall be well.

– Julian of Norwich

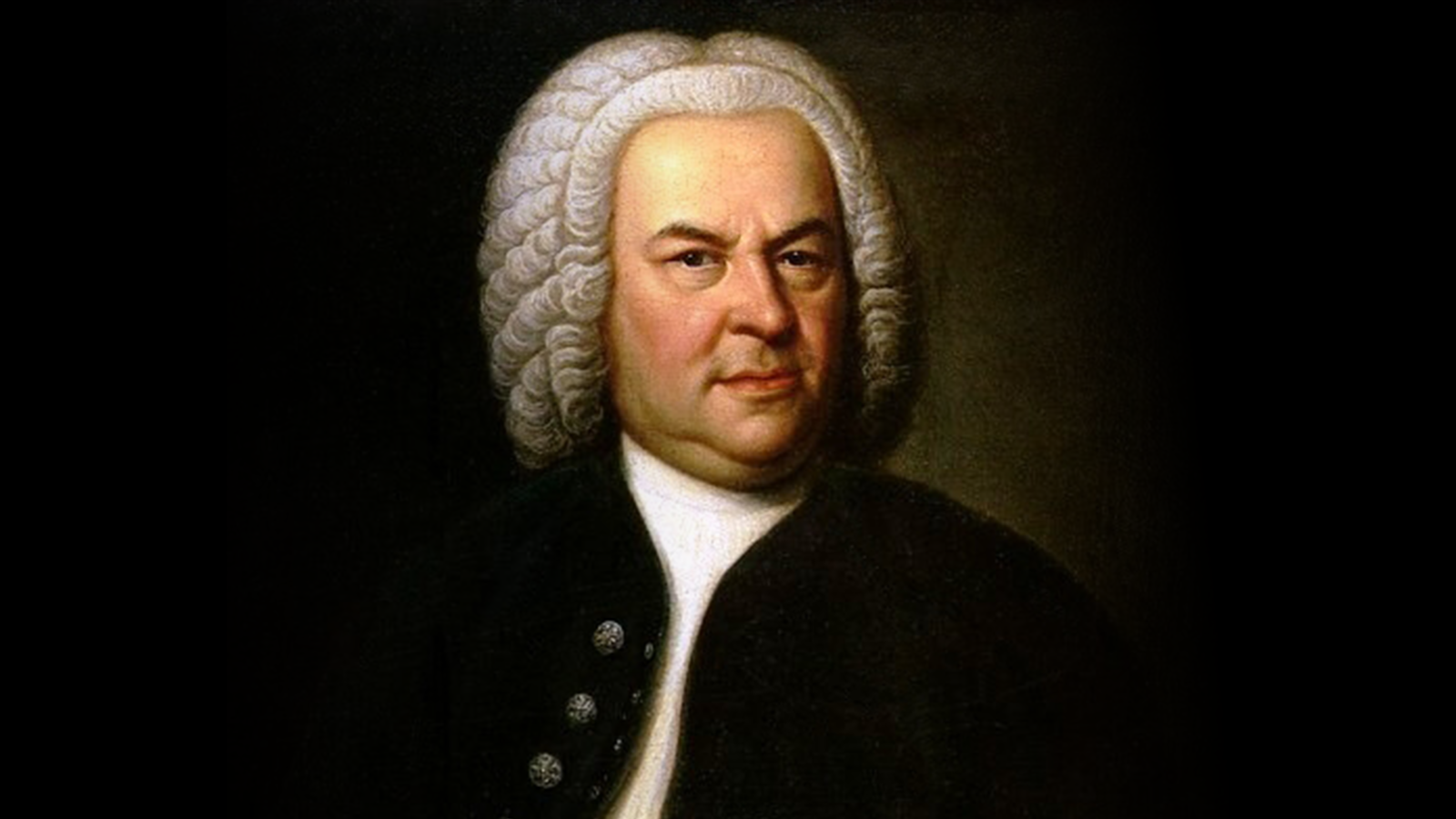

Johann Sebastian Bach and Arvo Pärt speak to the Wiradjuri in me. We are a breath of love. We are the spark of the divine. That is what enchants me in this music. A German composer and an Estonian Orthodox Christian – three centuries apart – can reach into my Wiradjuri soul and bring me face-to-face with God.

Pärt opens his Collage on B-A-C-H with a repetitive refrain. Discordant. A collision of sound. It is like the sounds in our heads, all our competing thoughts, jostling and pushing for our attention. All of the static electricity of our lives, slaughtering the silence – we can’t hear ourselves, how can we hear God? The music moves faster and faster, like our breath. Each pitch rises to the next. My throat feels constricted. This is Pärt’s pre-tintinnabular period, the modernist era of his creativity described by music scholar Benjamin Skipp as music that “observes its rationality at the expense of the audience”.

It slows and for a moment there is silence. Pärt takes me to a world of solitude. I glimpse God in a moonbeam, and I know – I truly know – what is real. I know what it is to be human – magically, mystifyingly human. I hold that moment until the noise starts again and Pärt sears my mind with the jagged sounds of the world.

Theologian Robert Sholl, who charts the connections between spirituality and music, says that Pärt “points to an excruciating gap between humanity and God”. The great artists know that God is in the reaching. I feel this in the Sistine Chapel in the Vatican. Michelangelo created the space between the outreached hands of God and Adam – they reach but do not touch. Here is the space for us to exist. God does not control our lives but leaves space for us to choose. Here in that space is all of our love and our hate, our peace and our war, our desire and our contentment – here we are a collision of humanity, capable of the worst and the best. Consonance and dissonance – the paradox of humanity – is what Pärt reveals to us.

Across the centuries Pärt and Bach have spoken to each other – a musical conversation that opens me to the glory of creation. In Collage on B-A-C-H and Bach’s Kanon zu acht Stimmen, they share the same breath. To Pärt’s insistence, collage and release, Bach responds with repetition, a monotony that refuses the world, that sits in a place from which we do not need to progress, in which we need no resolution. In the repetition is no escape, no change of scenery, no diversion. I am allowed to stay with God.

In my culture we have a word, Dadirri – to sit in the stillness, the deep quiet. Indigenous educator and Christian Dr Miriam Rose Ungunmerr Baumann calls Dadirri “the greatest gift we can give to our fellow Australians”. It is something we share with many ancient peoples of the world. Dadirri connects us with nature and God and brings us closer as people of God. Dadirri, she says, “renews us and brings us peace”.

I need not rush to the daylight. I can watch the platypus frolic in the moonbeam and hear the trickle of the water over the rocks.

Johann Sebastian Bach and Arvo Pärt speak to the Wiradjuri in me. We are a breath of love. We are the spark of the divine. That is what enchants me in this music.

The Absence of Evil

Bach was born into a world shadowed by catastrophe, 40 years after the treaties of Westphalia ended the Thirty Years War. The wars of religion devastated Europe. Villages were pillaged and burned. Entire populations vanished. Bach’s German homeland was a land of tribes. One of his many biographers, John Eliot Gardiner, wonders if Bach would have considered himself German at all: likely he would have identified as Thuringian or Saxon. His life was shaped by the land: in Bach’s case, the dense Thuringian forests. It was a haunted landscape that Gardiner describes as anabyss – “the emptiness of the primeval forests,” he writes, “with its undertones of demonic power unleashed by the long war”.

Bach’s music reflects his upbringing in the church. He was raised on Lutheran hymns praising Christ as the conqueror of death. Gardiner wonders if, like Bach’s fellow Thuringian Martin Luther, Bach had a fear of death. Certainly, he would know death intimately. It shrouded him from his birth in a war-torn land and the early deaths of his children – of 20, only half survived into adulthood. Gardiner says that many of Bach’s later works explored the dichotomy “between a world of tribulation and the hope of redemption”.

Australians are still traumatised by the shocking knife attack on defenceless, innocent shoppers on what was a normal Saturday afternoon in Sydney’s Bondi Junction. Six people were killed – five of them women – and I am left pondering the notion of evil. What all-seeing, all-knowing, all-loving God could sacrifice his children? There are no words at times like these. Music, art, poetry – these are the things that more gently speak to the soul. Bach’s Widerstehe doch der Sünde calls us to resist evil:

Stand firm against sin,

otherwise its poison seizes hold of you.

Do not let Satan blind you

for to desecrate the honour of God

meets with a curse, which leads to death.

The questions of evil and the nature of God are central to the work of Bach and Pärt. Gardiner says that Bach’s music is a “physical engagement with the bones and blood” of the story of the life, crucifixion and resurrection of Christ. Robert Sholl says of Pärt’s music that it is “the experience or institution of eternity”.

Simone Weil said that evil was the unreality that takes goodness from good. The French philosopher and mystic died at the age of 34, having fled the Nazi occupation of her homeland. She knew that evil lurked in affliction, “the chill indifference” that freezes our soul. A human being becomes merely a “thing”. Christ was crucified, she said, because he was “only God”.

Pärt answers Bach’s call to resist sin with his Fratres (Brothers), a composition that he says contemplates the space where everything unimportant falls away. “Time and timelessness are connected,” he says. “The instant and eternity are struggling within us.” In the Garden of Eden, time begins in an act of defiance.

The newcomers to our land did not see God in us. They could not see the divine in our country, our art and song. They thought they were bringing God to us, but God was here all along.

The unquestioned unity with the eternal is sacrificed for the world we can touch, the world we can know. Music releases time’s hold.

If we surrender to the sound of God, then perhaps we can hear ourselves.

The Death of God

My ancestors had our word for God: Baiyaame. When the strangers came to our land, a missionary asked where Baiyaame was, and my old people pointed to the sky. Baiyaame is in the stars, they said. The newcomers to our land did not see God in us. They could not see the divine in our country, our art and song. They thought they were bringing God to us, but God was here all along. What happens when God dies? God flees the Earth. And we are alone now.

Once I was past and future,

Now I am only the present,

Today, the moment,

and that is hard to bear,

With no past, no future.

– Bungal David Mowaljarlai

Bungal David Mowaljarlai was a Ngarinyin elder from Western Australia. To his people, he was the keeper of creation. His art, poetry and philosophy drew on the oldest collective memory of humankind, but he feared for the future. He watched the old stories disappear. Old men die, he said, and then all knowledge will be dead. We who are left will live with nothing. Mowaljarlai said that he felt crushed by time.

From the moment I read his words, they have never drifted far from my mind. I am haunted because Mowaljarlai was speaking from an annihilated place beyond the end of days. Death is not the worst thing that can happen. He had seen the end times and his torture was to go on living:

Once I walked my country

But lost my place

Then I lost my dignity – spirit.

Mowaljarlai felt the old-time people slipping from the world and taking with them all of their stories. Anthropologists came to record the stories but, he said, they did not go “all the way” back. They needed to go from creation to now, but would need a thousand years to piece it together. “The old-time people who knew that big story had died many, many years ago,” he writes, “I say we got no hope of ever knowing it now – these anthropologists can only study but they wouldn’t know where everything is written into the Country.”

Theologian Alexander Schmemann said love is sacrificial. “It puts the value, the very meaning of life in the other and gives life to the other,” he said. “We offer the world and ourselves to God.” We cannot understand Pärt without appreciating his Orthodox faith. He lives in the mysterio, the thinnest space between humanity and God. Sholl says the religious icon is a powerful representation of Pärt’s music: “through the fixed contemplation” of an image, we are drawn into a “deeper understanding of the meanings and significance of the Christian faith”.

Every day God greets us in a hundred small ways: an act of kindness, laughter, a kiss. And in music.

Forgiveness

Why do we look to the sunrise? Why does a baby instinctively clutch the fingers of a stranger and smile? Every day God greets us in a hundred small ways: an act of kindness, laughter, a kiss. And in music. Sit in the stillness, turn out the lights and listen … hear Pärt’s Vater Unser – the Lord’s Prayer. When I hear it, God is with me. I feel the presence of the creative love of the universe. Sung by a soprano, it soars – but played by a cellist it settles deeper into my soul. I know then – without any doubt – that Christ is risen.

Silence

The literary critic George Steiner warned us that the language of politics has become infected with obscurity and madness. “Unless we can restore to the words in our newspapers, laws, and political acts some measure of clarity and stringency of meaning, our lives will draw yet nearer to chaos. There will then come to pass a new dark ages.” The poet seeks refuge in muteness: “When the words in the city are full of savagery and lies,” Steiner said, “nothing speaks louder than the unwritten poem.”

In the past year, I have retreated into my own small space. Like too many, I suspect, I am battered by modernity. In a world of too much politics, there is nothing left to say. The bruised voices of the afflicted are drowned out by lies.

But in the silence is hope. Silence is not non-speech – it is a language unto itself. It is a language that cannot lie because there is no one to hear. In my silence, I have waited for God to speak. I sit in mass and I am transported to a place of magic. I am embraced in the corpus mysticum.

Some have criticised Pärt and his fellow “holy minimalist” composers for retreating and refusing the call to arms. In his repetition, solemnity and silence, Pärt is accused of not engaging with the world. But surely the world itself is an illusion. It has been since the Fall when we sought to know the mind of God and become God ourselves. We have swapped transcendence for a mirror.

For God to find us, we must subtract ourselves from time. We must live not in the death of the crucifixion but in the promise – the hope – of the resurrection. We must live in what has been called poetic mourning. It is the language of lament – a sigh too deep for words. Is this not the language of Bach? He places us at the foot of the Cross. His Jesus is the man of sorrows. Pain and sadness are a part of the human condition – and they are how we know joy and love.

We must live in what has been called poetic mourning. It is the language of lament – a sigh too deep for words. Is this not the language of Bach?

Beyond the creek where the platypus swims in the moonbeam there is a hill and there in a clearing is a careful arrangement of rocks; it looks like an ancient birthing site. All life is here – all there was and will be. In my garden, God returns from the stars and walks among us.

Here is my place of silence beyond the icy pandemonium of modernity.

My heart is in the highlands. My heart’s not here.

By Stan Grant

Stan Grant is a Wiradjuri, Kamilaroi and Dharawal man. He has been a journalist for 40 years, most notably with United States network CNN and the ABC, travelling to more than 70 countries and covering many of the biggest stories of our time. He has published several bestselling and critically acclaimed books and wrote and produced the acclaimed feature documentary, The Australian Dream, which won the Australian Academy Award. He has a PhD in Theology and is Distinguished Professor at Charles Sturt University.

Silence & Rapture tours to Sydney, Melbourne, Adelaide, Perth, Canberra and Brisbane. Click here to buy tickets – from $59, or $35 for under 35s and $25 for students.