When immersed in the creation of River, I had recurring dreams that Richard Tognetti would make me perform on stage with the Australian Chamber Orchestra, at an event like the one you’re at tonight. It was like one of those dreams where you find yourself naked in public. I also experienced these dreams during our earlier collaboration, Mountain.

I played the violin as a kid growing up in Canberra and performed in various school and amateur orchestras, but never to a high standard. At the end of high school I put away my instrument and haven’t picked it up since. Faced with the challenge of bringing a story to screen worthy of performance by this incredible orchestra, those long-ago days of performance anxiety came flooding back.

My love of music endured. Over the years I have attended many ACO concerts and watched the musicians with awe. To experience this young, dynamic orchestra in performance – Richard conducting with his eyes, his violin, and his movement – is to be transfixed. The ACO seems to me to be an orchestra of soloists, of individuals who have an uncanny ability to live and breathe as one organism and become the music.

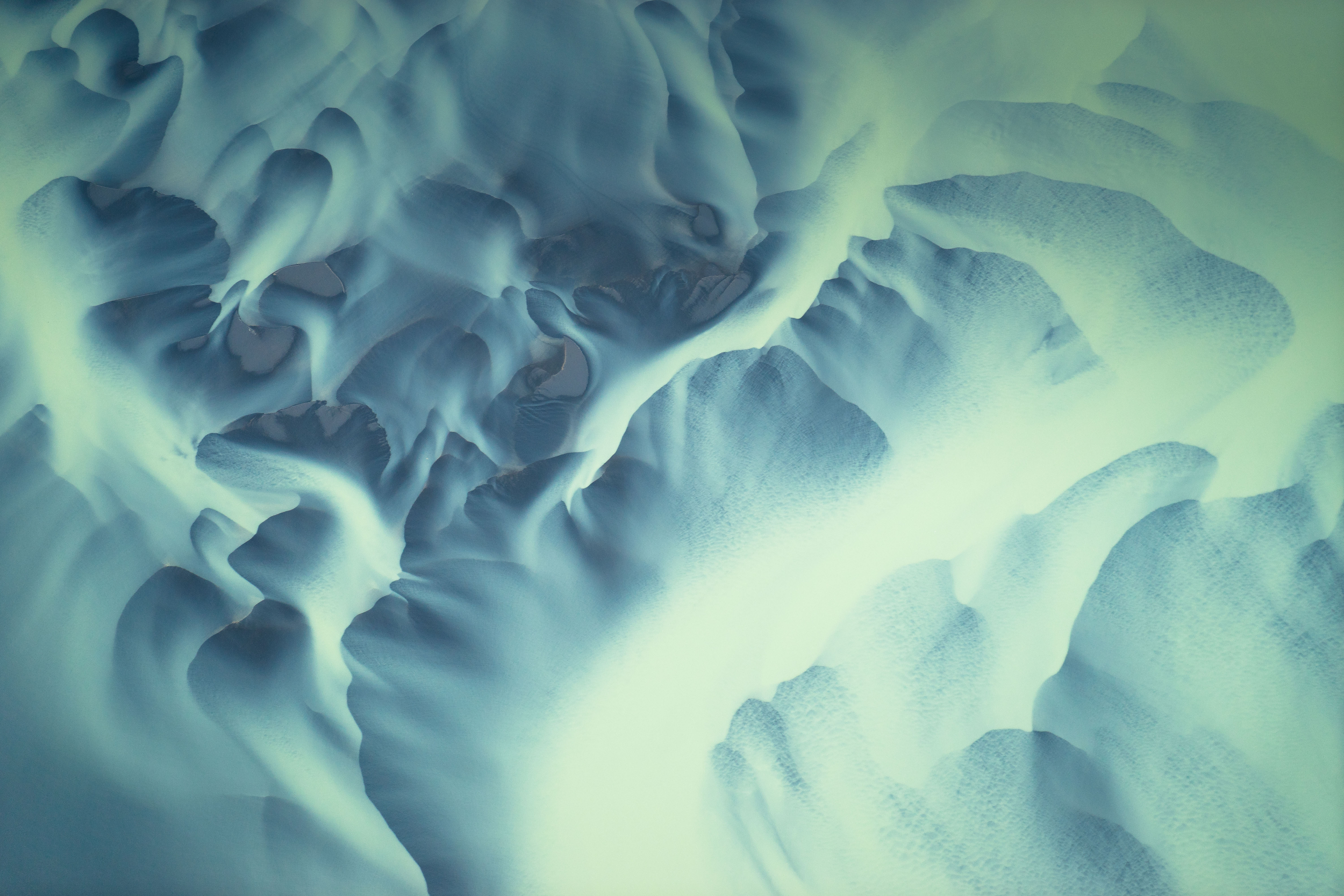

River tells the story of rivers through the ages. Central to the story is the fact that rivers are the arteries of the planet and were crucial to the development of human society. I often think about my responsibility as a filmmaker to respond to the climate crisis. This drove the making of River. Wild rivers are essential to support our growing populations, yet more rivers are dammed every day. Meanwhile, Sherpa friends who live in the upper reaches of the Himalayas are witnessing daily how the glaciers are shrinking and causing catastrophic flooding.

River was designed to inspire awe and wonder and connect people back to nature. My hope is that it can also play a role in helping us understand the dangerous consequences of our actions and how our future depends on the natural world. One thing we learned in our research for River is that when efforts are made to reverse the damage, it’s amazing how quickly nature can repair itself. We just have to give it the opportunity. This gives us all some necessary hope.

Like Mountain before it, River was conceived primarily as a concert film. While both films exist as standalone movies for cinema, they are designed for live performance. The recent boom in popularity of the cinema orchestra concert has seen E.T., Star Wars and Harry Potter films performed in concert halls worldwide; but few films are designed that way from the start. Having music in River’s DNA from the outset added tremendous technical challenges, but also an opportunity for close creative collaboration, which is one of the most rewarding aspects of filmmaking.

The foundation of the soundtrack of River is the existing classical repertoire. In general, this kind of music is very challenging to edit in a way that both maintains its integrity and meets the very specific requirements of film – its need for music to fit the length of scenes, for example, or to carry and influence the emotional responses of audiences. It’s no wonder that writing bespoke music for film is common practice. But I was privileged to be in partnership with the ACO, one of the greatest chamber orchestras on earth, and its artistic director Richard Tognetti, and that made all the difference.

Richard’s decision to include Johann Sebastian Bach’s Chaconne in River is a testament to both his determination and his extraordinary ability for arrangement. River includes an amazing drone shot, part of an early scene-setting sequence about the birth of rivers. When Richard saw it, he was adamant that he wanted to use the Chaconne, even though it is 15 minutes long and written for solo violin. For months he explored how he might make the piece work for the smaller ACO ensemble. I was initially sceptical, but every time I watch that sequence in the finished film I get goosebumps.

Richard also worked with the music of Radiohead guitarist Jonny Greenwood, Antonio Vivaldi, Gustav Mahler, Jean Sibelius, Maurice Ravel, Pēteris Vasks and Thomas Adès, making many fascinating creative decisions along the way. He is passionate about music, and he is passionate about providing his audiences with a transcendent experience in the concert hall. For any filmmaker, the opportunity to work with Jonny Greenwood’s music would be a thrill. The ACO commissioned Jonny to write Water in 2012 and the plan was always to include it. We initially placed it elsewhere in the film, but because it includes the Indian string instrument the tanpura, Richard felt it should sit with the scenes of funeral pyres on the edge of the Ganges in Varanasi, India. The result is spine-tingling.

About half the music in River is classical repertoire, with the rest original compositions written by Richard, Piers Burbrook de Vere and William Barton. The final soundtrack immortalises extraordinary performances by Richard, William and the ACO. One of the great joys of working on River was William Barton’s inclusion in the creative team. He has a peerless profile in the classical music world as an Indigenous composer, vocalist and didgeridoo player, and a long history with the ACO. The film explores the relationship between Indigenous cultures and rivers and Richard put us in touch after recognising William was the perfect talent to express this spiritual connection.

Richard, William and Piers collaborated over many weeks to compose what would become three cues in the film. When he arrived at the studio to record the final vocal track, William asked if he could take some time to respond emotionally to the film. What followed was an uninterrupted, improvised 15-minute vocal performance. When it was over I looked around the room, and we were all in tears. It is haunting and sublime. When he returned to the control room, he told me he had channelled his ancestors and ancestral ties to Kalkadunga country.

During the production of a normal film there is a clear chain of command, with the director sitting at the top. By giving the music more heft from the outset, myself and co-director Joseph Nizeti were, in effect, handing more control to Richard. For a film like this, where live performance is the end goal, this is at once essential and challenging. Treating the visuals and the music with equal weight adds another layer of intricacy to the already complex process of filmmaking.

My aim as a film director is to take the audience on an emotional journey, to make them think and feel. Most films follow human characters, but River doesn’t; the rivers needed to become the characters. My challenge as storyteller was to compel the audience to go on a journey with them. If by the end of the film, the audience cares about the fate of rivers, then we have succeeded. Sound design and editing also contributes of course: River’s editor, Simon Njoo, and sound designers Rob McKenzie and Tara Webb, helped achieve a cinematic language that is unique, magical and poetic.

The evocative narration, written with the extraordinary wordsmith Robert Macfarlane and performed by Willem Dafoe, is the final essential element. I was thrilled that both Robert and Willem returned, having been such important elements on Mountain. Sadly, due to Covid-19 our work together all took place virtually. There were many months on Zoom calls with Robert in Cambridge in the UK and with Willem while he was filming on location in Atlanta in the US.

William Barton asked if he could take some time to respond emotionally to the film. What followed was an uninterrupted, improvised 15-minute vocal performance. When it was over I looked around the room, and we were all in tears. It is haunting and sublime.

Joseph Nizeti, co-writer as well as co-director of River, was fundamental. During the making of Mountain I discovered Joseph’s strengths as a storyteller and he afterwards worked with us at our production company Stranger Than Fiction. His background as a musician made it a natural progression for him to step up beside me on River. He took the lead on the research, scouring the world for the best footage available, with great results.

How did I get tangled up with the ACO in the first place? In 2013 Richard was looking for a filmmaker to work on Mountain. We were put in contact by ACO cellist Julian Thompson, who is married to an old friend. I pretended not to be too excited, but I was so excited. I remembered being in the audience for the ACO film The Reef. I was struck by the diversity of the audience – classical music lovers sitting alongside surfers – and inspired by the possibilities of this type of production.

At that point, I had spent several years making films on mountains, including Everest, but Richard said that my film Solo – about the death of Andrew McAuley during his attempt to cross from Australia to New Zealand by kayak – particularly interested him. A keen surfer and skier, clearly Richard was fascinated by risk-takers and adventurers, and there we found our common ground. We are both interested in what drives people to achieve – and up for throwing ourselves into intense experiences.

During the making of Mountain, I realised Richard has more in common with risk-takers than I would have first thought. Watching him perform is like watching elite athletes lose themselves in a state of flow. As an artist he is a tremendous risk-taker, routinely pushing the boundaries of the classical music world. After accepting the gig on Mountain, I went off and made my 2015 film Sherpa. It began as an exploration of the disproportionate risks that Sherpas take every year, in assisting foreigners to climb Everest, and ended up documenting the worst disaster in the history of the mountain. Sixteen Sherpas were killed in an icefall as they carried supplies to higher camps. The experience undoubtedly informed the making of Mountain, which explores the nature of human fascination with mountains.

Having the experience as a filmmaker to watch your film with an audience is always a thrill, but to see it performed live in a concert hall is an experience I will never forget. I’ll always be grateful to Richard and the ACO for that opportunity. Thinking back to those recurring dreams, I realise now that they stopped after the first performance of Mountain. I’m hoping the same will happen with River!