Written by Daniel Keene

1.

In what often seems an increasingly atomised world – and especially after the isolating and alienating effects of the Covid pandemic protocols – attending a concert to listen to music has become a singular kind of event: a conscious decision to gather with other people in a common space to share a particular inclination, to satisfy a collective hunger. But we gather in that space to enjoy what is, finally, a private experience.

We listen alone but in the presence of others. We come to the concert hall to satisfy a personal desire with others who have the same need to engage with the pleasure of music, but we will each leave with our own impressions and responses to the music we have heard together. The orchestra shares that space, that time, that air with us, but their experience is very different from ours. The music we hear is the reason for their artistic practice, it lives in their intellect and their understanding of how to express the music’s emotional possibilities. Out of this knowledge they will sculpt in sound a moment that stimulates or cajoles, that lulls, excites, delights or moves their audience. The energy exchanged between those who play and those who listen – that tangible connection – is an ancient, never changing, ever human and humane phenomena.

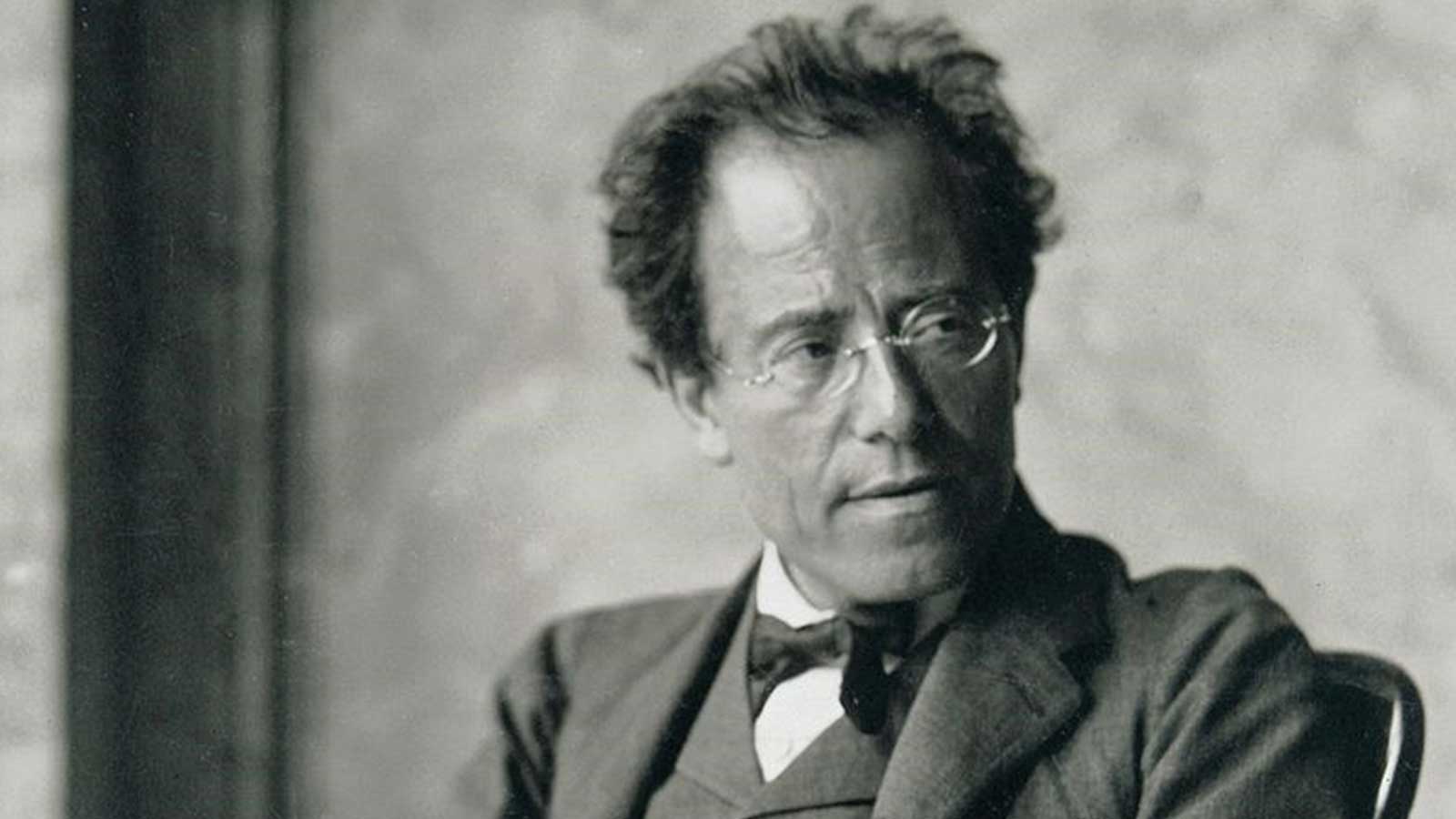

For much of his life Gustav Mahler earned his living as a conductor. During his six years at the Stadttheatre in Hamburg alone he conducted no less than 744 performances. Composing was an almost part-time occupation. He is reported to have said that “what is most important in music is not to be found in the printed notes”. It was the performance of the work that mattered, especially when it came to his own music, which demanded large orchestras, symphonic choruses and operatic soloists. He often requested many more rehearsals that the orchestras he worked with were accustomed to, unifying and shaping the sound of the ensemble, setting the tempo, structuring the phrasing, closely guiding the interpretation. It seems particularly true for Mahler that this was as much a part of his creative practice as his initial setting down of the notes.

I have never attended a live performance of Mahler’s work. My encounter with his music will be a solitary affair, my concert hall a pair of headphones, the presence of my orchestra something imagined. I will listen to the nine completed symphonies, the unfinished 10th and Das Lied von der Erde. It will simply be me and the music. In 1904, writing to Oskar Pollak, the writer Franz Kafka – himself a German-speaking Bohemian Jew like Mahler – informed his friend that his firmly held conviction was that “a book must be the axe for the frozen sea inside of us”. Kafka is speaking of the transforming and liberating potential of art, insisting that it must confront and break through the denials and refusals we may hold onto in our inner selves, awakening our emotions and thoughts.

2.

Like Kafka’s axe, the music of Mahler insists on this awakening. His symphonies invite us into a world that sounds at one moment like the crashing of tectonic plates moving under the surface of the earth and, in the next, the sweet, high song of a lark. The symphonies are never anything less than a complete, multidimensional world. Notwithstanding Mahler’s use of text – prayers, dramatic extracts or poetry employed to illustrate or express certain narratives or emotions – his symphonies do not merely tell a preordained story or illustrate an imagined scene: they are essentially an experience of meaning being created through a series of startling transformations.

Or perhaps they could be called revelations. Because these transformations, some sudden, some slowly evolving, are always a kind of epiphany. They develop out of what is inherent in the music itself, as if they were nascent, always there waiting to be revealed. They can be surprising, yes, but they also always seem inevitable.

The energy exchanged between those who play and those who listen – that tangible connection – is an ancient, never changing, ever human and humane phenomena.

The symphonies sustain themselves with their own continually generated energy, creating their own dynamic, their own context. They are nothing but themselves: the apprehension of a possibility that transcends the limitations of the quotidian in which the listener is immersed in insistent, deeply human expressions of longing, of grief, of hope, of love, of creation itself.

The opening of the first symphony is a deep, reverberating hum. Rising out of silence, it is the other-worldly sound of music coming into existence. It lasts a few moments, calling into being all that will follow. It is a sound taking us into a world where some other force is already threatening to erupt. It creates a kind of unsettling calm, an ambient disquiet. You can feel it in the pit of your stomach. It shakes you. You listen: perhaps this is what the act of creation sounds like.

Particularly in Mahler’s first three symphonies, certain passages of music might suggest something like the formation of a star out of cosmic darkness or water cascading down a mountainside. But he isn’t fashioning an image of a star or a waterfall. It is the sound of the power unleashed at the moment of the star’s making, the weight and force of the water’s fall. It is sound reaching for the ineffable, wanting to express creation itself; life coming into being and persisting.

For me, this is where the sacred resides in Mahler’s music: not the sacred expressed through music created for the celebration of the divine, but music that celebrates the sacredness of life, of being, of music itself.

The opening of the first symphony is a deep, reverberating hum. Rising out of silence, it is the other-worldly sound of music coming into existence. It lasts a few moments, calling into being all that will follow.

Mahler’s religious beliefs seem ambiguous. Facing a rabidly anti-Semitic administration, he converted from Judaism to Catholicism in 1897 to better improve his chances of gaining the position of principal director of the Vienna Hofoper (the court opera). He got the job.

He would say in later years that this decision cost him a great deal. Turning away from the faith into which he was born would be, as it would for anyone, a difficult, wrenching choice. But what was he turning to? He never became what could be called a practising Catholic. His choice was not about religion; it was about music. In his position at the Hofoper he directed countless operas, conducted numberless symphonies, introduced new composers to his audience and continued to compose. Music was his spiritual home. If for some of his audience his music spoke of a divine being, if for them it praised their God, then that praise was born out of Mahler’s vision of the sacred – and his vision of the sacred was his own.

3.

In the 2023 recording of Mahler’s second symphony by the Wiener Philharmoniker, conducted by Gilbert Kaplan, there is a moment close to the end of the final movement when you can hear a deep intake of breath as the male chorus prepares to sing the final two words of the text. The preceding lines are sung softly, almost whispered:

tremble no more, tremble no more

prepare yourself...

And then the enormous, audible intake of breath before:

...to live!

I hear that breath as part of the music, as much as the voices themselves and the words they sing. That booming exhortation to live feels like the heart of this work. It is not so much a forceful encouragement as an outright demand. This part of the text was written by Mahler. It follows and takes its inspiration from an eight line poem, “Arise, yes, you will arise from the dead” by Friedrich Klopstock, which is sung in the opening of the fifth movement of the symphony.

As with this demand to live, there is a repeated insistence in Mahler’s music that we do not despair, that we have no right to abandon hope, no matter how faint or distant it may seem. Continually throughout his music themes unfold, seem to collapse and are then remade. If sometimes there is a foreboding ambience thrumming beneath lyric phrases that suggest love’s bounty or a celebration, as if beneath the paradise of Eden there may lie an abyss, there is just as often a sense of healing light rising triumphantly out of darkness, the sacred nature of life striving to assert itself. Implicit in this assertion is that destruction contains the seeds of resurrection, that life can defy death, that the tragic is not an end but a new beginning.

4.

Mahler’s Das Lied von der Erde is considered by some to be his ninth symphony but, although he sometimes privately referred to it as his ninth, he himself never used that term in public. This was because Beethoven, Schubert and Bruckner all died before or while writing their 10th symphonies and Mahler wanted to avoid this curse. By disguising it as a song cycle, even though it’s structured as a symphony in multiple movements with various tempos and tonalities, he thought to cheat fate.

This superstitious sleight of hand, however, failed: Mahler did not live to complete his 10th symphony. Das Lied von der Erde is a setting of six poems from the “Golden Period” of Chinese poetry (Tang dynasty, 618–907). Though some traces remain of Chinese imagery, we are very far from China in this work. Translated into German from earlier French translations, their transposition into European languages gave them a whole new meaning; they are European creations, and Mahler’s settings make them very much his own.

Das Lied von der Erde opens with a short, bright flourish that introduces an explicit expression of what is often central in Mahler’s work – the never-ending struggle between hope and despair, light and darkness.

Dark is life, dark is death . . .

But the wine is golden and plentiful. Now is the time to drink and enjoy what you can, sorrow is always drawing near... As male and female voices alternate throughout the piece, everything in this work centres on ideas of balance: between waking and sleeping, drunkenness and sobriety, leave-taking and homecoming, losing then finding a friend, fading away and rebirth in the cycle of the seasons, living and dying.

This work contains some of Mahler’s gentlest, most lyric passages. There is less turbulence than in some of his earlier work, and more opportunities for solo instruments to emerge from the ensemble with a single theme delicately expressed. But even in the midst of this beauty, there are moments of bleakness, of surrender. In the second song of the cycle, “The Solitary One in Autumn”, a lone figure laments the weariness in her heart. The small lamp that she carries has “gone out with a splutter”. The song finishes as she asks:

Sun of love, will you never shine again,

Gently to dry my bitter tears?

In the final and longest song, taking up almost half of the duration of the piece, this same voice, alone as ever, yearning for a companion, is still able to experience the beauty and abundance of the world: the soft grass, the breathing of the earth, the song of the brook.

Nothing has seemed rushed, nothing forced, but something has been transformed, reshaped and made anew.

O beauty! O eternal love –

life-drunk world!

The music heightens this sense of finding relief from sorrow. At times it drifts under the poems in slow, dark waves, only just managing to keep the words afloat; at others it rises energetically, lifting the text into a celebration of life’s (sometimes drunken) pleasures.

Taken as a whole, Das Lied von der Erde can be considered as a single song, rising and falling as suffering and delight, sorrows and blessings, follow one after the other in the course of a life. But it ends on a sustained, lyrical note of hope and renewal that fades gently to silence:

The dear earth everywhere

blooms in spring...

Blue light in the distance!

Always... always...

5.

There is something that happens to time when listening to Mahler’s symphonies. So much can happen in a few heartbeats that you wonder how on earth did you get from a moment when the music hits you like a gigantic, roaring wave, to this instant when you hover in a tranquility that seems to float just above a bottomless silence. Nothing has seemed rushed, nothing forced, but something has been transformed, reshaped and made anew.

It is these metamorphoses that propel the music, that accumulate one upon the other. It is this accumulation that creates the emotional weight of the symphony. The music continuously builds up inside you. You cannot linger, or hope to hold on to any one moment: you are already being drawn towards the next. This momentum creates a kind of pressure: you are held between what you have heard and what is yet to come, between what follows you and what is approaching.

It is this pressure that breaks the sea of ice, that awakens your response, that calls up what cannot have been expected, because you have never been in this moment before with this sound breaking over you like a storm or touching you as softly as the caress of a loved one’s hand.

If that is what happens, then in the silence that falls at the close of the symphony your response will probably remain unspoken. In the end, words seem a poor reply to the call of music.

Stuart Skelton and Catherine Carby star in Mahler's Song of the Earth, directed by Richard Tognetti, and touring to Sydney, Melbourne, Brisbane and Canberra. Click here for tickets.

Daniel Keene is a Melbourne playwright whose work has been widely performed nationally and internationally. His accolades include two Victorian Premier’s Literary Awards, three NSW Premier’s Literary Awards and the Sidney Myer Performing Arts Award. More than 100 productions of his work have been presented in Europe, predominantly in France, and he is the first (and so far, the only) Australian playwright to be produced in the main program at the Avignon Festival. In 2016 Daniel was appointed to the rank of Chevalier de l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres by the French Ministry of Culture