Written by Kate Holden.

Kate Holden is a writer and the author of two acclaimed memoirs, In My Skin and The Romantic, and non-fiction book The Winter Road.

Fanny Mendelssohn Hensel, her younger brother Felix Mendelssohn, and Frédéric Chopin form a tender, soul-suffused and outrageously talented trio at the heart of the Romantic music of 19th-century Europe. Each was gifted from birth, each a prodigy carefully cultivated by the finest mentors to perform in salons aglow with gilt and satin; each was acclaimed during their lifetime, and each made profoundly beautiful, profoundly personal music beloved for, by now, about 200 years.

With bright, emotional eyes and elegant pallor, the Mendelssohn siblings and Chopin were all physically vulnerable but robust in their devotion to music: their thin, clever fingers dashed over piano keyboards with restless and searching ripples of melody, and their alert minds constantly puzzled over and listened internally to yet more ravishing music. But they all died young, within two years of each other, as something in their bodies gave way: Fanny and then Felix of the family fatality, stroke; Chopin probably of pericarditis associated with tuberculosis. Their conjunctions were scant, their efflorescence brief and gorgeous. This program lets them meet again.

There are curious symmetries between the three apart from their first initial. Born within a year of each other, Felix Mendelssohn and Chopin each had an older sister (Fanny and Ludwika) alongside whom he was first taught piano by his music-loving mother, then expert tutors.

Family relocation to big cities early in life made a great difference. While the Mendelssohns and their two siblings grew up wealthy on an estate in Berlin, attending their parents’ salons and playing before the artistic and scientific elite of the city, the Chopins moved from the Polish countryside to live in a Warsaw palace that housed the Conservatory for which his father worked. They all matured in a lustrous world. There was no question that the boys’ gifts would be recognised, that they would be famed musicians.

For Ludwika and Fanny the plan was marriage, with music on the side. But all were somewhat shy, and while the women made do with private recitals, those candle-lit, silk-lined rooms were the setting that Felix and Chopin instinctively preferred. Yet the music made there meant something different to each of them.

Fanny (pictured above), the eldest of the three musicians, was the first and the last to be recognised. Her father Abraham had once imagined the young girl as the superior success but qualms about the propriety of a woman in music denied that destiny. She pressed, but even her admiring brother held that line. Though late in life she burst into publication regardless – to be belatedly approved by Felix – it has taken until the last 50 years for her music to finally flourish.

A glorious revelation, it surges supple and satined across piano keyboards, or aches and trembles in string. It is easy to sense within it the full soul of a woman who, though she married happily and mothered proudly, grew up in a loving family and was kept in wealth and comfort through a torrid historical period, still tilted restlessly towards vivacity and desire. For three decades her music lived largely in the prestigious salons held first by her parents and then herself.

She too had been ambitious: at 17 she wrote, “up to the present moment I possess [Felix’s] unbounded confidence”. But in adulthood life pressed around more snugly and her father told her, “music will perhaps become his profession, while for you it can and must be only an ornament”.

Her private piano performances were breathlessly acclaimed – at the age of 13 she performed from memory all 24 preludes from Bach's The Well-Tempered Clavier – and still she wrote music in the quiet of her rooms: mostly chamber music, fit for her environment and options. She composed more than 250 lieder, an orchestral overture, chorales and choruses and by the age of 19 she’d completed 32 fugues. Her String Quartet in E-flat major was written in 1834 at the age of 28, when she was married to artist Wilhelm Hensel and mother of a four-year-old son. By then Felix had shown some of her songs to an admiring critic in London: her first public notice as a composer.

Waylaid by domestic life over subsequent years, she watched her gifts totter but determinedly straightened them, saying that, with her loving husband on the other hand urging her to go public, she felt like a donkey between two bales of hay. By 1846 she’d daringly published a collection of songs under her married name, though she confided to a friend that “if the matter comes to an end then, I also won’t grieve, for I’m not ambitious”. Her construction as suffering artistic genius plays, it has been pointed out, into an expected Romantic trope, and she didn’t seem to suffer anguish so much as regret. But she never quit her music and it still sounds out –adventurous, sometimes lavish, always subtle, fully realised and brilliant, with the extraordinary Mendelssohnian appeal.

She composed more than 250 lieder, an orchestral overture, chorales and choruses and by the age of 19 she’d completed 32 fugues.

It was a particularly distinctive brand, closely forged. Fanny and Felix played together; shared a devotion to Beethoven and Bach; met Goethe and set his words to music; aligned with a traditional and somewhat conservative philosophy of music; and exchanged thousands of letters in such deep concord that, as one biographer observes, it is difficult to know who authored which. Their passion for each other was, typically for profoundly gifted people, ardent and intense: when Felix was forced to miss her wedding Fanny wept, with his portrait near her, and wrote, “every morning and every moment of my life I shall love you from the bottom of my heart, and I am sure that in so doing I shall not wrong Hensel”.

He called her “Minerva” after the Roman goddess of wisdom and published six of her songs under his own name – arguably not in appropriation but stealthy promotion, even swallowing the infamous incident when his good friend Queen Victoria, asked to name her favourite of his compositions, nominated one that was in fact his sister’s. He wrote: “I tell you, Fanny, that I have only to think of some of your pieces to become quite tender and sincere. You really know what God was thinking when he invented music.”

Fanny counselled, advised, collaborated with, encouraged, edited and adored him. While directing rehearsals for one of his cantatas in 1847, she was felled by a stroke, aged 41.

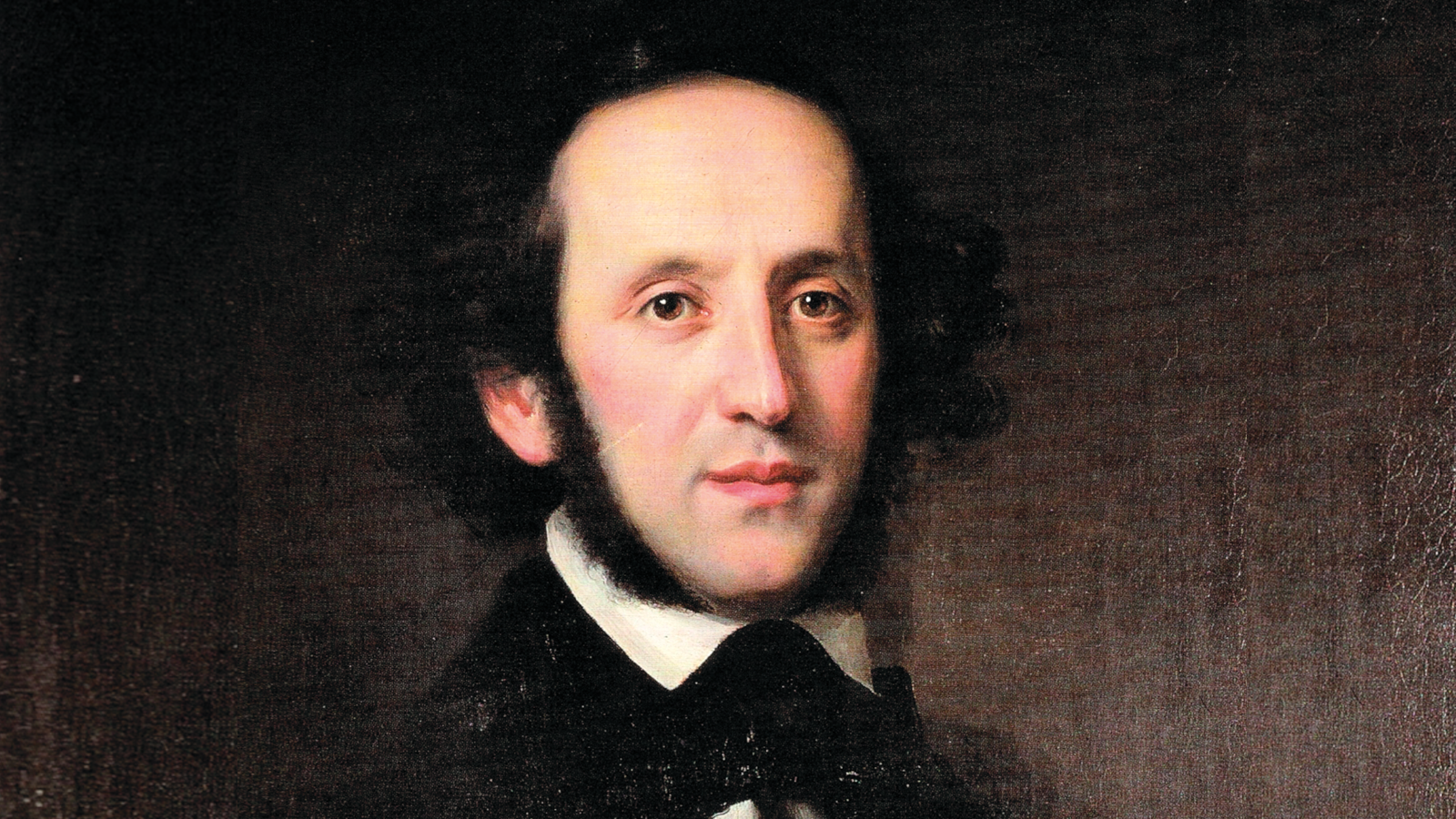

Felix (above), a neat, sure man with watchful brown eyes, lived a blessed life of more open doors. Considered, in the words of critic Charles Rosen, “the greatest child prodigy the history of Western music has ever known” – apparently even more accomplished than Mozart – Felix studied aesthetics under Hegel, was tutored by Carl Friedrich Zelter and Ludwig Berger, a student of Clementi, and the originator of the nocturne, John Field; was cherished by Goethe; and wrote his first works as a young child. Between the ages of 12 and 14 he composed 13 string symphonies and many chamber works.

His first full symphony (in C minor, Op.11) was penned at 15 and his maturity as a composer is said to begin the following year with his String Octet in E-flat major. The Concerto for Violin and Piano was written in that adolescent spill of inspiration in 1823. The previous year the baptised family had changed their surname to Bartholdy, a break from the Jewish heritage Abraham felt constrained by, and Felix had had his first work published, a piano quartet. The next year he would be mentored by composer, virtuoso and friend of Beethoven, Ignaz Moscheles, who said he could hardly find anything to teach him.

At 20, Felix found fame as the primary reviver of his beloved JS Bach, and soon travelled widely on the wings of his reputation.

Conscious of his debt to the past and his implicit Jewish identity in middle Europe, music for Felix would be expression, challenge and, especially, assertion.

Felix ventured from comfortable Berlin to the welcoming worlds of other cities in Germany, England, Scotland, Italy, and positions in Düsseldorf and Leipzig. His music was performed on grand stages and celebrated in one of the most astonishingly stellar music scenes in history alongside Schumann, Liszt, Berlioz, Chopin and others. But he preferred small, intimate circles of family and friends, where his lively personality and warm humour shone and his terrible temper was forgiven. Fanny’s husband drew a satirical illustration of the Mendelssohn world as a wheel: Felix the hub, the sisters and friends as the spokes, a self-reliant and reassuring cosmos.

His blazing reputation and output spoke of generous foundations and thoughtful respect for elders such as Bach, Beethoven, Mozart and Haydn, a disciple of legacies rather than radicalism: critic Richard Taruskin characterises his version of Romanticism as “‘musical ‘pictorialism’ of a fairly conventional, objective nature (though exquisitely wrought)”. Conscious of his debt to the past and his implicit Jewish identity in middle Europe, music for Felix would be expression, challenge and, especially, assertion. He remains hugely popular and among the corpus of his beloved classics are works such as the Overture to A Midsummer Night’s Dream, which includes his iconic “Wedding March”, his Italian and Scottish symphonies, the Songs without Words for piano and his funeral march played in the late Queen Elizabeth II’s cortege procession.

Having previously seen each other perform, Frédéric Chopin (pictured below) met Felix Mendelssohn in 1834 at a music festival in Aix-la-Chapelle, when Felix had invited the Polish exile to Düsseldorf. They spent “a very agreeable day” playing and discussing music at the piano. Felix, amused, felt a bit like a staid schoolmaster and thought Chopin and his friend suffered “from the Parisian sickness of despair and quest for passion” – an astute prediction about the notoriously distressed and sensitive Chopin. Felix considered Chopin “the perfect musician” and admired his keyboard skills.

The two men met only once more. It seems perverse that they weren’t closer friends: both slight and somewhat introverted, they shared the experience of precocious success, obsession with piano, a boyhood in grand houses, visits to Scotland and infatuation with the famed Swedish singer Jenny Lind. Chopin had begun his public career at the age of seven, composing two polonaises that same year; by 1829, when he was 19 and wrote his Piano Concerto No.2 in F minor, he was finishing his studies, had begun composing his Etudes, been to Berlin to see – but not to meet – Felix in concert, and returned to what would be his last year in Poland.

Chopin had fallen in love with a singer, Konstancja Gładkowska, “whom I dream of, who inspired the Adagio of my Concerto”. The piece was played at his farewell concert in Warsaw before he left on travels, when revolution broke out in Poland. He was never able to go home and settled in Paris – Gładkowska apparently forgotten – into his legendary life as an unnervingly pale and haunted genius, questing exile, lover, elusive, even diabolical sensation and classic Romantic figure. His incomparably limpid music, always for a piano and running like a glinting stream through every era of melancholy poetry, every pensive evocation of the 1830s and every rainy afternoon since, is unforgettable; his white hands seem always rippling over keys, his agitated passion always falling towards a sonorous silence that seems full of something imminent.

Felix had described death as a place “where it is to be hoped there is still music, but no more sorrow or partings”. His generally happy life was demolished in 1847 when he received news of Fanny’s sudden death. He was already weary from decades of work and withdrew further, cancelling concerts, intensifying his preoccupation with expression in music, planning operas but despairing stoically of his future. He knew he was broken. He visited Fanny’s former home, cancelled the German premier of his Elijah, wrote one last song – the sorrowful Altdeutsches Fruhlingslied – for Fanny, and died after strokes that November, six months after he lost Fanny. He was only 38.

Less than two years later, Chopin followed him into the dark.

The lives of Chopin and the Mendelssohns were short, formed like their own small, exquisite works of chamber music: enclosed, restively dynamic, their few elements – privacy and reputation, travel and home, isolation and companionship, ambition and sensitivity – contrasting and recombining and, with the legends as with the melodies, still resonant with such feeling, such loveliness.

Chopin & the Mendelssohns tours 9-22 November. Click here to discover the program and book tickets.