It was Good Friday, but Venice hadn’t missed a beat all day. With her gondolas, cupolas and shimmering façades, Venice is above all a spectacle and has been for 500 years. That day’s spirited performance had begun at sunrise, Jesus’ death at Calvary notwithstanding.

What, I wondered, would be a fitting way to round off a Good Friday in Venice? In her heyday in the Middle Ages, Venice was much more than a stellar performance with Oriental flourishes. Once upon a time the Queen of the Adriatic had made Byzantium and then the Turks tremble. It may be the outlandish displays of opulence in art and architecture from those centuries that still bedazzle us – the Byzantine domes atop St Mark’s basilica, the fantastical façades along the Grand Canal, peeling and many-hued, all washed in the city’s quivering, watery light – but there’s a later Venice, more Baroque, more flamboyant, more bizarre.

Some sort of burst of Baroque brilliance seemed appropriate, something vertiginous, but in a setting harking back to distant Araby. What is Venice, after all, if not a “colossal souk”, as the art historian Giuseppe Fiocco famously wrote? It was an Eastern bazaar for half a millennium, after all, it was the city where Antioch and Alexandria came to Europe – or at least their produce and wares did, their shapes and pigments, their mathematics and philosophies.

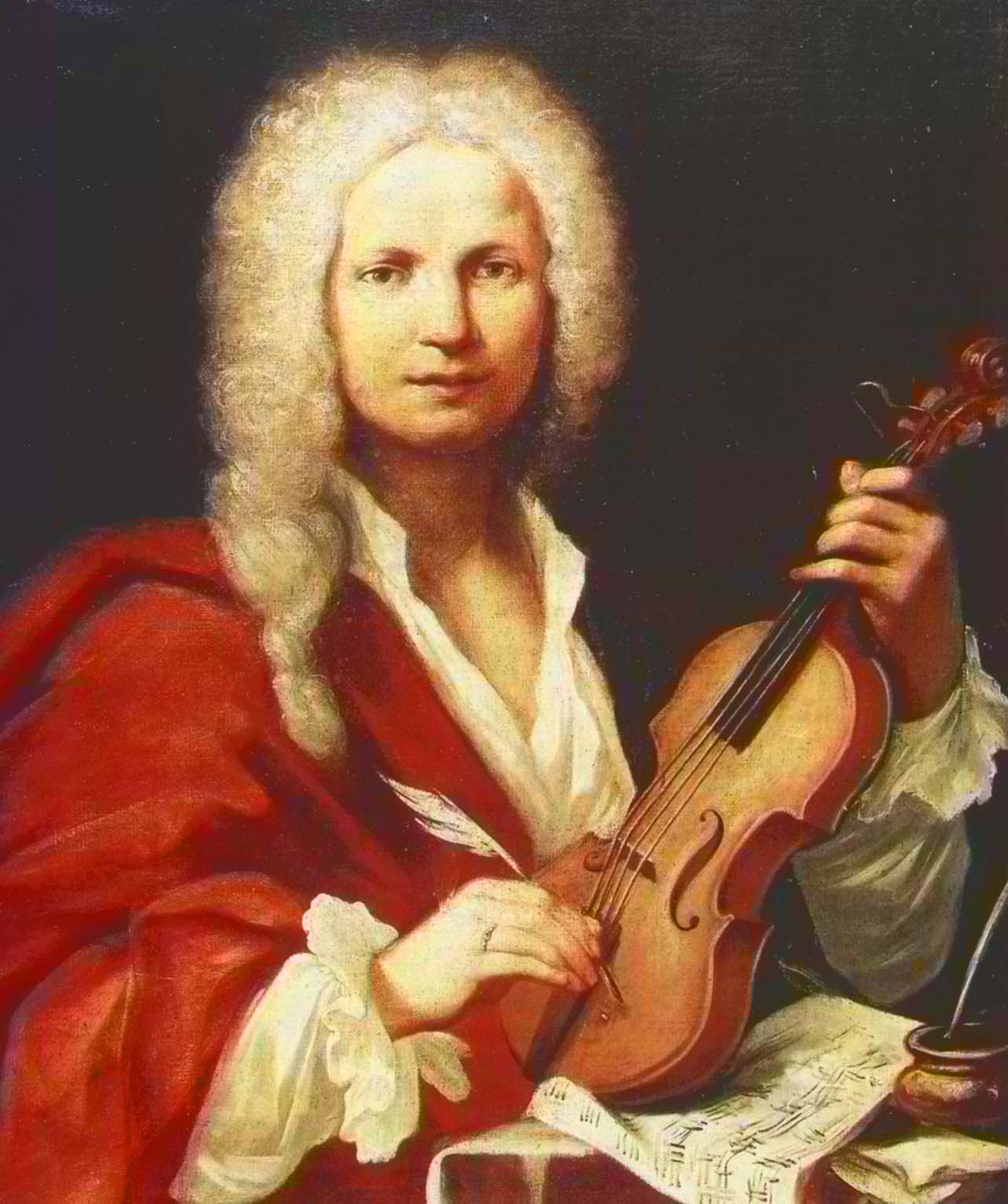

Of all the things to choose from in Venice that evening, Vivaldi at the Scuola Grande di San Giovanni Evangelista (the confraternity of St John the Evangelist) in the Levantine tangle of back streets and piazzas near the Rialto, seemed perfect. The Scuola Grande was founded by a group of Christian flagellants nearly 900 years ago when whipping yourself in public was still all the go. It houses to this day a miracle-working splinter of the True Cross. When it fell into the canal at the Bridge of St Lorenzo, it was miraculously retrieved before a crowd of hundreds. The spectacle has been depicted in brilliantly coloured canvases by many artists, including Gentile Bellini, one of the founders of European Orientalist painting. Bellini actually lived and worked at the Sultan’s court in Constantinople for some years as Mehmet II’s “Golden Knight”. To ask whether or not any miracles ever happened is not a Venetian question. A performance took place – that is the point.

At the top of the grand staircase at the Scuola Grande, I discovered a vast, richly ornamented Baroque salone with chairs set out on the floor of red, white and black marble beneath a frescoed ceiling. Surrounded by Tintorettos, a Tiepolo Apocalypse, and a statue of St John himself writing his gospel, my spirits soaring, I sat in wonderment, listening to The Four Seasons, the Red-haired Priest’s exuberant show-piece.

The designer of that magnificent room in the Scuola Grande, Giorgio Massari, knew precisely how brilliant his Baroque refashioning of an ancient salone was, just as Vivaldi knew precisely how breathtakingly brilliant his capriccios were – and, for that matter, just as Venice knew how unparalleled her own extravagant beauty was. That’s what a virtuosic performance allows. We collude in the caprice. And so for me on that doleful day in Christian memory everything came together perfectly: a performance of The Four Seasons in a room that was itself a performance of courtly frenzy, the very embodiment of what Vivaldi was loved for, created as it happens almost simultaneously with Vivaldi’s four concerti. (And the birth of Casanova – who else?)

*

By the 1720s, when Vivaldi and Massari completed their respective masterpieces, the city itself had become a trading and military backwater, a kind of fabulous stage-set for fashionable tourists. In 1844 Charles Dickens caught the flimflammery of Venice in her declining years very nicely when he wrote to a friend that the “gorgeous and wonderful reality of Venice is beyond the fancy of the wildest dreamer”. No draft of opium, he wrote, could have fabricated such a place.

There had, however, been a spectacular golden age to decline from. In the 9th century the Doge carried off a sensational coup by enshrining St Mark’s miracle-working relics, carried off by two Venetian merchants while visiting Alexandria, in the new basilica he’d built for it on Christian soil. “We’ll happily trade with the Eastern infidel,” this purloining of the saint’s relics seemed to say, “but we are staunch defenders of Christianity”. The Pope later did what he could to make the Venetians abjure trade with unbelievers, but it made them so stupendously rich they couldn’t resist.

Indeed, in succeeding centuries, Venice became the richest entrepôt in Europe. In the medieval period the city on the lagoon imported spices from as far away as the Moluccas, right on Australia’s doorstep, to be used in European kitchens, medicines and nostrums. Venice also imported cotton, carpets, ceramics, raw silk and ash for glass-making from the Near East. Ironically, the source of the greatest wealth amongst the spices was not nutmeg or cloves, but pepper: pepper, like Venice herself after 1500, exists largely for show – or, more precisely, for sensual enjoyment and for its mystique. The myth persists that pepper was sought after to keep meat fresh, but at root, like outrageously expensive wines today, its main function was to trumpet the social status of those who offered it to their guests.

For the early part of the millennium Venice also sold to the East. Many cities at the eastern end of the Mediterranean contained Venetian merchants’ colonies– trading posts with warehouses, lodgings and even churches – where Venetians bought from but also sold to Arab lands. Antioch, Jerusalem, Damascus, Aleppo, Cairo, Alexandria, Byzantium and some cities further afield all had active Venetian colonies busily buying and selling.

What did the Venetian merchants sell to the East? Salt at one time, as well as soap, paper, armour and some woollen garments, but also human flesh. Indeed, live bodies were the most precious merchandise of all. Later a musical and artistic hub, Venice was first a slave-trading hub where slaves from the Black Sea in particular – Russians, Georgians, Circassians – but also African slaves from the Mediterranean coast of Africa were sold on in bulk to the Arabs in the late medieval period for vast profits. The Venetians themselves liked a slave or two about the house as well – no patrician family could do without a retinue of slaves, convents owned slaves, even artisans used them in their workshops.

Venice itself was not a melting-pot, it was an emporium. The city may have looked like a smorgasbord of ethnic or cultural diversity, but it was in fact a vast market owned and frequented by Christians. It was not “multicultural” in the modern sense at all.

Around the middle of the millennium something started to go seriously wrong with the pepper and spice trades. Venice may still have smelt of pepper, but the peppercorns themselves were now mostly in Seville.

Western Europe had no need of Venetian middlemen to exploit its colonies in the New World. It had no need of Venice to import its cinnamon, cloves, nutmeg and pepper either, because Vasco de Gama had opened up a marvellous one or two-stop spice route to the East that by-passed the Mediterranean entirely. Lisbon and Antwerp became the great trading hubs, smelling of pepper and cinnamon, the once-empty Atlantic became the crowded route to riches beyond all imagining, the Ottomans took over the Venetian and Genoese trading posts in the Crimea, and even Slavs went out of fashion as slaves, to be replaced by Africans, which the Ottomans had much better access to from Mozambique to Algeria.

So the Queen of the Adriatic, with an elegant flourish, did the only thing a queen with a shrinking realm can do: although still the richest city in Italy, La Serenissima became a tourist attraction. Royal families everywhere are still doing it.

It didn’t happen overnight – it took 300 years – but well before Vivaldi burst onto the scene, almost everything in Venice was theatre, a refurbishment, a re-enactment, a re-picturing of the past for the fashionable tourist trade. It became a favourite stop-over for young British aristocrats abroad on their Grand Tour, eager for a character-building combination of culture, high-stakes gambling and debauchery.

When they wanted to blur the line between the fantasy of power and the less glamorous reality, Europeans often resorted to a touch of the Orient. Hans Holbein the Younger, for instance, had once painted Henry VIII as an Oriental monarch, bedecked with jewels, standing on an Oriental rug – powerful, overwhelmingly male, almost a sultan (but not quite). Now Venice, too, decked herself out in Oriental finery – the colours, the gilding, the shapes, aromas, silks, carpets and tiles of the East – to fool the public and herself. By the time Vivaldi composed The Four Seasons and Massari designed the salone in the Scuolo Grande, Venice was more or less exactly what she is today: a cosmopolitan tourist hub that knows how to put on a good show.

Although music and singing were said to fill the air in Venice in the 17th century, and it was in Venice that the first commercial opera house in the world was opened, what stands out about the 18th century now is the flowering operatic tradition. Vivaldi alone wrote scores of operas. Ticket prices plummeted, new opera theatres were opened all over the city and the opera season was (unsurprisingly) timed to coincide with the Carnival, the most famous extravaganza of licentiousness, lavish performance and Baroque decoration in Europe.

If they weren’t at the opera, Venetians were painting or out buying Europe’s best. Venice is full of canvases by Europe’s great masters, from Mantegna and Memling to Modigliani: they’re everywhere. However, Venice had her own school, including Tintoretto, whose utterly terrifying vision of Paradise still hangs in the Doge’s palace. “The most precious work of art of any kind whatsoever, now existing in the world”, Ruskin called it.

In Vivaldi’s day the Venetian school had a final surge of creativity, favouring colour over line (that was Florence), a predilection inherited from the Near East, going back past Titian to Bellini, the Sultan’s Golden Knight, in the 1400s. The subjects were not Oriental, but the colours and shapes were. Its influence can still be felt to this day in Manhattan and Berlin. Along with Tiepolo (father and son) and Canaletto, the painters who stand out in this final burst of colour and light include Marco Ricci, an international art sensation whose luminous landscapes (also “capriccios” in a painterly sense) inspired Vivaldi to compose The Four Seasons.

In Venice you found virtuosity wherever you looked - although scant virtue. It was a radiant paradise for the right kind of pleasure-seeker, although not in Tintoretto’s sense. It became the most visible city in the world. Since then nothing much has changed.

The Four Seasons, inspired by the colours of Vivaldi's Venice, tours to Canberra, Brisbane, Sydney, Melbourne, Adelaide, Perth, and Wollongong, 11-27 March. Click here to buy tickets.