Written by Emily Bitto.

Emily Bitto is an award-winning and widely published writer of fiction, poetry and non-fiction. Her debut novel, The Strays, was the winner of the 2015 Stella Prize. Her second novel, Wild Abandon, won the 2022 Margaret and Colin Roderick Award and was shortlisted for the ALS Gold Medal. Emily has taught literary studies and creative writing at various institutions over the past decade and is currently a tutor and course advisor at the Faber Writing Academy.

Many readers will be familiar with Dr Samuel Johnson’s famous declaration that “a man who has not been to Italy, is always conscious of an inferiority, from his not having seen what it is expected a man should see. The grand object of traveling is to see the shores of the Mediterranean.” In fact, Italy functions as a symbol for the very longing to travel – for the “life elsewhere” – itself: a seduction to which artists have perhaps been especially prone.

In 2018, before the pandemic made travel impossible for a while, I was awarded a BR Whiting Studio residency by the Australia Council for the Arts, which allowed me to live and write for six months in an apartment in Trastevere, Rome. The apartment was originally owned by Lorri Whiting (née Fraser), a Melbourne-born abstract painter, and her husband Bertie, a poet. The Whitings left Australia in 1955 and never returned, remaining in Italy for the rest of their lives. After Bertie’s death in 1988, Lorri donated the apartment to the Australia Council to be used for a writing residency.

Implicitly, this bequest is founded on the belief that travel, and openness and exposure to other places, other cultures and other artistic traditions, is beneficial – if not essential – to an artist’s development. Perhaps it is also predicated on the idea of Italy as the cultural centre, a locus of art and culture that will inevitably seep into the soul of the visiting antipodean artist and elevate her work. While this may be a particularly Australian attitude, closely related to our longstanding tradition of “cultural cringe”, in projecting our fantasies onto Italy in particular, we are not alone.

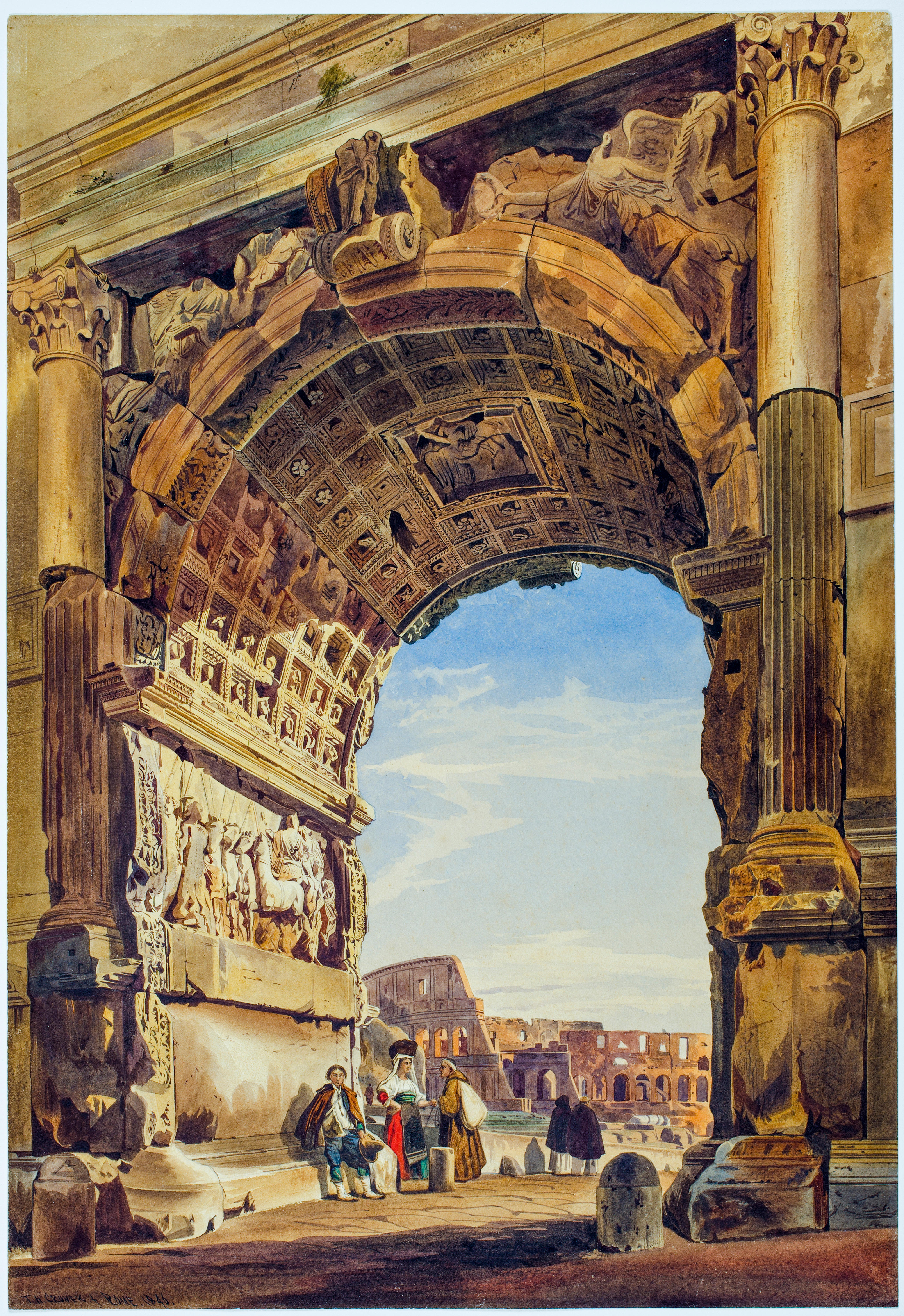

The Arch of Titus and the Coliseum, Rome, 1846, by Thomas Hartley Cromek.

Undoubtedly this is in part due to the cultural domination and colonising reach of the Roman Empire. But if what we now refer to as Italian culture has historically exerted such influence over artists and their creative output, it is likewise true that artists – whether painters, writers, musicians, filmmakers or photographers – are essential to the idea of a particular place that accumulates over time within the cultural imagination. Italy is no exception.

When I arrived in Rome, I brought with me a panoply of images, assumptions and fantasies about the place and culture that, on reflection, were influenced far more by the literary representations produced by non-Italian writers – from the English Romantic poets Lord Byron, Percy Bysshe Shelley and John Keats, to Henry James, Thomas Mann and especially, in my case, to Australian literary Italophile David Malouf – than by either factual research or by accounts created by actual Italians. From the English Romantics I had absorbed the idea of Italy as a locus of the sublime, as well as the idealised image of literary pilgrimage or “grand tour” – though because both Keats and Shelley died young in Italy, there is a certain fatal (though not unromantic) tragedy in the associations that cling to their representations.

Its irony notwithstanding, this poem created a yearning in me, long before I actually reached Italy, to attach myself to the lineage of the artist-traveller.

From Henry James I assimilated the idea of Italy as the apex of taste and beauty, layered with history, and complex almost beyond capturing: a place against which the oldest human dramas of power, desire and morality play out with a fitting sense of grandeur and significance. From Mann’s Death in Venice, its tale of decadence, desire and death set against the watery ineffability of the sinking city, I envisioned a place that seemed to belong more to dream than reality. And from David Malouf I imbibed a particularly Australian fantasy of Italy, characterised by an excruciating sense of distance and the image of the Italian journey as an essential rite of passage. This is at its seductive, if self-deprecating, height in the final lines of Malouf’s poem, “The Little Aeneid”:

…With the epic two days out from land, a thousand

lines break loose, the apron

strings of a suburban

Dido snap, the new life

beckons—a coast whose every promontory

glitters with artefacts, plains

all air, by moonlight ghostly

with stick-white asphodel.

In your loins the dragon

howls for empire. Time

like a new land awaits

your entry. Give it

a name. Three syllables: say, Italy

Its irony notwithstanding, this poem created a yearning in me, long before I actually reached Italy, to attach myself to the lineage of the artist-traveller: to return, like those before me, altered by my encounter, and perhaps even to contribute my own representation of Italy to the great corpus.

Johann Sebastian Bach is another artist on whom the influence of Italy and Italian culture was mediated by absorbing the work of other artists.

According to literary critic Michael L. Ross, this dual aspect – the light and the dark – is at the heart of artistic representations of Italy: “Few [places],” he observes, “have been more copiously productive of ambivalence.”

Johann Sebastian Bach is another artist on whom the influence of Italy and Italian culture was mediated by absorbing the work of other artists. Because of his commitments to court and church, Bach was never able to travel to Italy, but he maintained a fascination with the musical developments of the country throughout his life. During his 20s and 30s, he spent countless hours seeking out, copying and arranging manuscripts by Vivaldi, Marcello and others, regarding them as an opportunity to refine, test and expand his compositional toolkit. And he continued to derive creative stimulation from Italian concertos into his later life: his ‘Concerto in the Italian taste’, as the Italian Concerto was officially titled, was published when he was 50.

Duomo Santa Maria del Fiore, Florence, Italy.

Lu’s description of the quintessentially Italian elements of the work – that is, those that bear the influence of Bach’s absorption of Italian music and musical trends – is informative. She contrasts the newer, Italianate elements of the Italian Concerto with Bach’s earlier style, characterising the former as “light-hearted”, “natural”, “youthful”, “relaxed” and “immediately appealing”, and the latter as more densely woven, “intellectual”, “complicated” and even “labored”.

This set of duelling adjectives maps onto the opposition between the ideas of north and south, with the south evoking associations of warmth, sunshine, bountiful nature and a sensuousness that veers towards decadence. Opposed to this is the idea of Bach’s native north as a place of cold, formality and austerity. In the words of Ross, for the northern artist, Italy embodies a fantasy of “personal freedom that transcends, while it includes, artistic licence” and at the furthest extreme, “the unrestrained public enactment of the emotions and appetites”

On a later visit he writes, “I sat for a long time in the Sistine Chapel – an absolute miracle. For almost the first time in my life I was enraptured by the art of painting.

In contrast to Bach, another of the northerners on the program, Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, spent significant periods of time in Italy and was profoundly influenced by the place and its culture. In a letter describing his first visit to Rome, Tchaikovsky writes: “Strolling around the city I actually saw the sights of the capital, i.e. the coliseum, the thermae of Caracella, the Capitoline, the Vatican, the Pantheon, and, finally, the acme of celebration of human genius, the Cathedral of Peter and Paul [sic].” The adverb “actually” is telling here, as it alludes to the fact that these were places already alive in his imagination, which he was now, at last, able to view with his own eyes. On a later visit he writes, “I sat for a long time in the Sistine Chapel – an absolute miracle. For almost the first time in my life I was enraptured by the art of painting.”

Tchaikovsky’s ideas of “Italianness”, which inflected his Souvenir de Florence, are thus clearly characterised by great admiration and reverence for its art and architecture. However, in another letter, he too seems to conceive of Italy as a culture marked by extremes of both light and dark, civilisation and decadence. On the same trip, during which he gazed in rapture at the Sistine Chapel, Tchaikovsky witnessed that most potent symbol of Italian decadence and licentiousness, the carnival. “We have a carnival in full swing here,” he writes. “I only knew this from Berlioz’s [Roman Carnival Overture], and I can tell you that it well conveys the cheerful ebullience of the Roman crowd. He who hasn’t seen this cannot imagine what a demonic frenzy this is.”

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky

In his survey of literary representations of Rome, Florence and Venice, Ross concludes that these opposing binaries are the essence of what constitutes “Italianness” for foreign travellers and artists. Delving a little further into the specific tropes that cluster around these three cities reveals a rich and fascinating lexicon of image and symbols.

Florence, Ross observes, is represented via the binary between paganism and Christianity, which expresses itself even within the city’s architecture, with the black and white patterning of many of the city’s church facades itself playing out the symbolic victory of enlightenment over an earlier “dark” pagan past. Venice is symbolised by the palace and the prison described in Canto IV of Byron’s Childe Harold, between the grandeur of the city’s longfamed wealth and history and its fading future as memento mori. Finally, Ross classifies Rome as a place in which limitless extent, in time and space, coexists with the idea of the centre, roughly coinciding with the contrast between antiquity and modernity.

In weighing all of these various and competing symbolic images of Italy, it strikes me that they may all be summed up in the Italian term chiaroscuro, with its implication that contrast is necessary to show each competing aspect to its best effect.

To complicate the picture still further: as well as functioning as the very symbol of the fantasy of travel, another important facet of the idea of Italy appears to be that it is a place – perhaps the only place – that is able to live up to – even surpass – the fantasy of which it is the symbol. After poking fun at his juvenile longing to journey to the cultural centre of Rome to find “the real thing”, Hughes continues by earnestly declaring that “nothing exceeds the delight of one’s first immersion in Rome”.

Street in Venice, 1882 by John Singer Sargent. National Gallery of Art, Washington DC.

My own experience of Italy confirms this. While in residence at the BR Whiting Studio, I was forever gasping at the storied sites that greeted me at every turn. I visited Naples, Sicily, Pompeii, the Amalfi Coast, Lake Como, Tuscany, Venice and Piedmont. I experienced not one moment in which I thought that the idea I had of the place, gathered from all those writers who had been here before me, was grander or more beautiful than the place itself.

However, like all fantasies, Italy has its shadows. Due to the failure of the Italian government to upgrade their waste disposal system by the date when the EU banned incineration, piles of uncollected rubbish littered the streets of Rome during the months I spent there. Scores of refugees, mostly from North and Sub-Saharan Africa, begged or set up illegal stalls on street corners. Those I spoke to were trying to get to Germany, where they at least had a hope of being granted refugee status and allowed basic work rights. At the same time, the far-right education minister was proposing to exclude history from the high school exit exams, with the result that its prominence in the curriculum would steeply decline.

And so I too continue to reinforce the tradition of representing Italy as a chiaroscuro – or perhaps more accurately, as a place upon which visitors and the artists who continue to be inspired by it, persist in projecting their own ambivalent fantasies. Fortunate, then, that the program for this concert also includes work by two actual Italians, to offset all this fervent fantasising.

Postcards from Italy tours 14 - 26 September. Click here to discover the program and book tickets.