Richard Tognetti knows that for non-Spaniards, including him, Spain comes with built-in expectations – “probably all the clichés that we know” – from food and temperament to movies and landscape. And music. “It’s all about the rhythm, it’s all about the sultry sensitivities that are able to be slipped into music somehow to create a sense of geography,” Tognetti says. He goes further, asking, what is that geography? Does it imprint itself on outsiders? Do you even need to go to Spain to feel it or can you get it just by – work with me here, he says – listening to the sounds of people talking?

“Often that’s where the colours of music come from, especially the French. I teach myself French and the more I am able to speak it and read it – badly, of course – the more I realise the nuances of the language are so important. I think that’s an integral part of it, the way people speak and what the language means with different nuances of the sounds.” Given that the ACO’s program Sketches of Spain is rich with interpretations of Spain by composers and arrangers from France, Italy, America and Russia – some of whom knew the country intimately, some filtered through the works of others – how does this language theory translate musically? “We can say in very specific ways Janáček took from the spoken or verbal utterances of human beings and turned it into music, but I suppose my hypothesis must be if you speak...”

Tognetti pauses, searching for the right example. “This flight attendant once came to me and started talking about music, seeing that I was a musician, and said ‘I’m totally un-musical’, and something happened, a vocal exclamation, and I said there, you just sang, you just made an utterance. “If you can speak, you’re musical, so therefore it’s just a matter of expanding that into a musical language. That’s one thing. Then there’s geography, and the way people travelled and what they brought back.”

There are many cultural and geographical layers to the selection of music in Sketches of Spain. For example, Italian-American composer and pianist Chick Corea (pictured, bottom), who drew inspiration for his masterpiece, Spain, from Joaquín Rodrigo’s ‘Aranjuez’ Concerto, first explored it through Gil Evans and Miles Davis’ interpretation of the 2nd movement in the 1960 album Sketches of Spain. “At the time I was in love with Miles’ Sketches of Spain… I still am,” Corea said towards the end of his life.

The cellist and composer Luigi Boccherini was born and educated in Italy and moved to Spain as an adult. Georges Bizet trained and worked in France and Italy, while Claude Debussy and Maurice Ravel lived and worked in Paris. Rodion Shchedrin, whose lively, condensed reinterpretation of Bizet’s opera, Carmen, carries its own excitement – “he’s made a wicked little suite there,” Tognetti says approvingly – was Moscow-born and educated. So, Spain, yes, but via a group of non-Spaniards interpreting the work of non-Spaniards influenced by Spain.

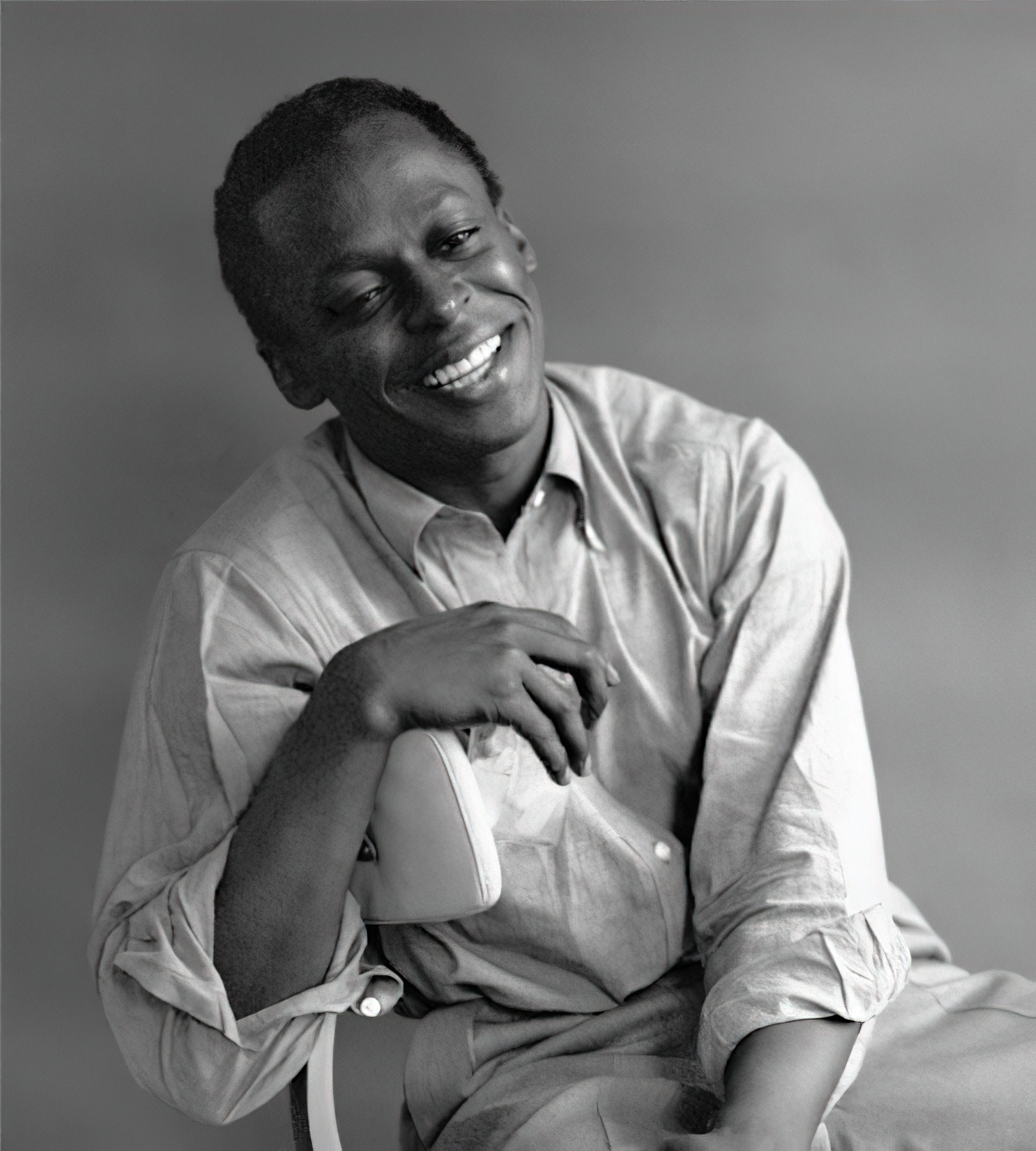

“That’s particularly true of Miles Davis (pictured, below) and Gil Evans. Though Ravel came from [the Basque region in southern France, bordering Spain] so he must, again, have imbibed that spirit. He was regarded as French, but the Basque separatists would say he was Basque,” says Tognetti. “Once again, he picked up on the way people spoke and found the rhythms in the speech and the rhythms in the landscape before he moved to Paris and became a universalist, so to speak.”

As with Spain itself – for centuries at the juncture of Western Europe and Africa, of Christian and Islamic thinking and architecture, of the Old World and the New – the intersection of composed music, classical traditions and jazz is the fulcrum of the program. It ranges from the so-called “Third Stream” fusion of jazz and classical music to one of the giants of jazz, Davis, whose own explorations across nearly 50 years took in almost every 20th-century musical form.

Central to the journey from Ravel to Corea is Sketches of Spain. Credited to Miles Davis, the piece is built on the arrangements of Gil Evans, who composed several of the tracks, and is almost defined by its use of space and an elegant melancholy. However, Evans’ piece, Solea, finds its rhythmic pulse as a relatively optimistic counterpoint. “I call classical music, ‘shut up and listen music’, because it just doesn’t work when you’re not actually listening,” says Tognetti. “And it’s the same with Solea. There is that sense of space, and also that sense of strangeness that both Miles and Gil Evans were able to bring. And we have a personal connection with Gil Evans because Maria Schneider [an American composer whose work the ACO has premiered in Australia a number of times] actually worked with Gil Evans, and she talked about him in such high terms, that he really understood what purpose that instruments play and how to get a different space out of them.”

To play the jazz-based compositions, the ACO is augmented by a quartet led by pianist Matt McMahon, with trumpeter Phil Slater, bassist Brett Hirst and percussionist Jess Ciampa. “We collated the program thinking, who the hell are we going to get to play it? And remember when this program was collated [during Covid lockdowns], we were thinking global and acting local,” Tognetti says of the guest musicians. “We asked them early on, would you feel challenged and comfortable by taking this, and their answer was yes.”

According to McMahon, his response was more like “hell yeah!” He says he has listened to the ACO in the past and thought how much he would love to participate in the “colours” he could hear in an orchestra as adept at challenging themselves as any jazz ensemble. “It’s really exciting,” McMahon says. “Oddly enough, I’ve watched them a lot over the years and that’s one of the great things that they have: this really solid, wonderful playing of traditional repertoire and then this vision of trying to include other things and take risks and go for something different. That’s a really exciting thing to be part of.”

The willingness to examine a piece from every angle, including the problematic – to be free with unexpected juxtapositions, where “it’s all in the mix” – is an attitude McMahon is familiar with, calling it “just a certain way of thinking” or maybe, a way of being. “With jazz there may be a composition that has a certain chord structure and we improvise over that chord structure. There will definitely be some of that. And then in a wider sense, improvising can happen on a song, any kind of material, or improvise on nothing at all, which is something [we] have done a lot of,” says McMahon. “So there’s a kind of a spectrum of ways of approaching it. There probably won’t be much totally free playing, but maybe one or two moments where that might happen.”

Tognetti says that the colours, the cross-currents, the composers – indeed the essence of Spain as realised through these pieces – is at its heart a balance of freedom and control. He sees that balance in Corea and others in “the greatest age of jazz, arguably, when jazz became art music and there was a liberation”. But not everyone understood the message. “The Third Stream was great because it really opened up many doors and at the same time created a certain discipline and restrictions, which you’d need, otherwise you’re just a hippie on the streets of Byron,” he says. “Nothing wrong with that, but you’re not going to be in the great jazz class of the world. You need restrictions, as in rules, like how harmony proceeds. And if you are going to break those harmonic rules you need good reason.”

Rather than a potential breaking point between theoretically free from-rules jazz and supposedly tied-by-those-rules classical, it is the common ground he argues, the starting point. “Coltrane and Davis, and Evans, being an arranger, knew those rules and restrictions and were able to break them. Chick Corea, like Keith Jarrett, came out of, and in awe of, the harmonic rules that had been passed down and codified and developed by Bach,” says Tognetti. “I can’t think of any jazz musician who’s worth anything who didn’t like Bach. And if they didn’t I would immediately dismiss them. That’s where Chick Corea comes from … and therefore it was possible for him to build a monumental orchestral landscape out of his talents and abilities.”

Click here to buy tickets and learn more about ACO 2022: Sketches of Spain. Purchase single tickets, Purchase single tickets from $49 or book Sketches of Spain as part of a Full-season Subscription and save up to 60%.