Ástor Piazzolla, the man who took tango from dives to concert halls, once said, “for me, tango was always for the ear rather than the feet.”

As Piazzolla stretches his bandoneon – a type of concertina popular in Argentina and Uruguay – the moaning sound creeps beneath the skin and pulses with air that feels like light.

In 1965, writer Jorge Luis Borges and Piazzolla collaborated on an album of tangos and milongas called El tango, featuring Piazzolla’s smoking bandoneon. Borges writes: “To rhythmic playing, he could tell stories of the things he had seen, beneath the awnings of Adela, and in the brothels of Junín.”

The origin of the tango is mysterious. The musical gatherings of slaves in the Río de la Plata basin were called “tango” or “tambo” and were often banned by colonial authorities. In the late 19th century, tango began to emerge from the bordellos and dance halls of the impoverished areas of Buenos Aires, the home of large populations of African descendants. By the early 20th century, tango had drifted from the slums to the cities on barrel organs and in theatres, rapidly shattering the conservative norms of the era with sexual energy. The dances were loaded with sensual thrusting and pulling. The musicians felt like they were gambling. And the lyrics were dusty and sad.

Buy tickets to ACO 2022: Piazzolla

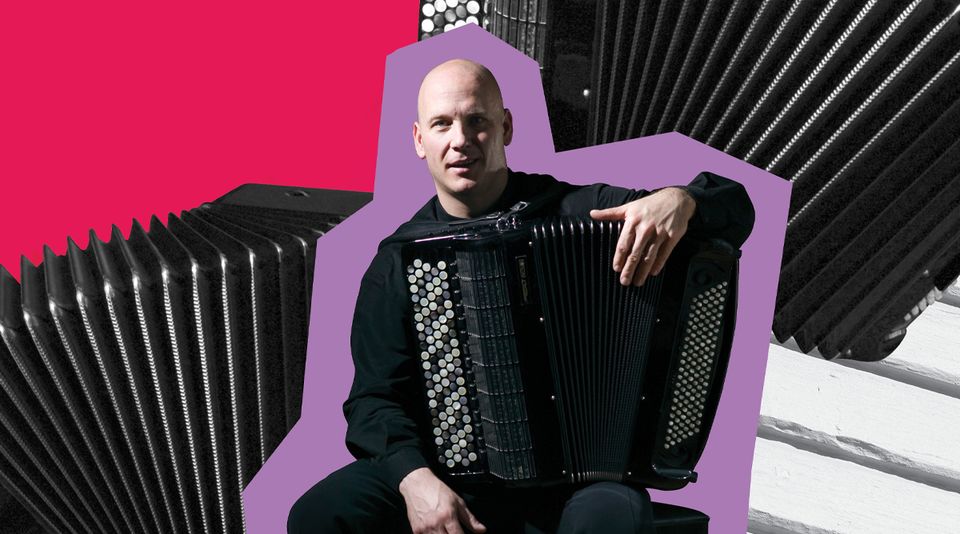

In 2002, classical accordion virtuoso James Crabb led a national tour of Piazzolla’s work with the Australian Chamber Orchestra. “That was probably the first national tour of a Piazzolla concerto in Australia. So the response of the audience was that it was absolutely spellbinding,” says Crabb. “There’s a lot of nerve in Piazzolla. It can be brutal, violent, and it can be incredibly romantic or sad. It’s an emotional rollercoaster.”

Throughout his youth, James would hear his father play Scottish folk music on the accordion. “There was this sound of the instrument in my life from a very early age. There was something that attracted me to the buttons and the way the instrument moves.”

When he was four years old, James pestered his parents for a little red piano accordion and began attending music lessons. By the time he was a teenager, James was playing in folk bands and discovered the essence of his practice, “It wasn't camaraderie, because I was probably 40 years younger than everyone else on the stage, but it's that chemistry which is the magical thing. When the chemistry is there, this unwritten understanding of what you’re trying to achieve together, that still follows me today.”

When Piazzolla was two years old, his family left their home on the port of Mar del Plata in Buenos Aires for the United States. The family eventually landed in Greenwich Village, Manhattan, where his father Don Vicente (Nonino) worked as a barber. After his eighth birthday, Nonino bought him a bandoneon from a pawn shop.

In an interview, Piazzolla said, “[My father] brought it covered in a box, and I got very happy because I thought it was the roller skates I had asked for so many times. It was a letdown because instead of a pair of skates, I found an artefact I had never seen before in my life. Dad sat down, set it on my legs, and told me, ‘Ástor, this is the instrument of tango. I want you to learn it’.”

On the streets of New York, surrounded by hustlers and gangsters, Piazzolla was raised on jazz of the 1930s. The swinging bars, nightclubs and dance halls roared with the music of Louis Armstrong, Fats Waller, Billie Holliday and Duke Ellington. At home, his father’s record collection featured Carlos Gardel’s tango records and Bach.

When he was 13, Piazzolla made his film debut with Carlos Gardel. “The only pleasure I had was appearing with him in some scenes of El día que me quieras – I played the role of a newspaper boy – and backing him, on certain occasions, with the bandoneon that I was just beginning to study,” writes Piazzolla in his autobiography A Manera de Memorias. “To understand and love Gardel, you have to have stayed in Buenos Aires, to have visited the Mercado de Abasto, and I was only a 13-year-old kid that lived in New York.” As an outsider, he was searching for who he was. He played in quintets and travel back to Buenos Aires to join Aníbal Troilo in one of the greatest tango orchestras of that time.

When Piazzolla was awarded the Fabien Sevitzky award for Buenos Aires Symphony in Three Movements a fight broke out in the audience because there were bandoneons in the orchestra. He was awarded a scholarship to study classical music in France and decided to leave tango and his bandoneon behind.

As James outgrew the limitations of the piano accordion, he discovered the classical accordion and followed a different path. He decided to part with the free spirit of folk bands and undertake classical training in the Royal Danish Academy of Music in Copenhagen with classical accordion pioneer Mogens Ellegaard. “Well, even though [Piazzolla] didn't actually write to the classical accordion, you know, we just think of ourselves as members of the same family, members of the aerophone family,” says James.

As a student, he came across Piazzolla’s Ballet Tangos for accordion. “Our world was really transcriptions, mainly Baroque music, and then completely contemporary original work for classical accordion,” he says. “[Ballet Tango] written for Four Accordions became a hit for accordionists as an introduction into that whole world. It was just such a hybrid form of music.”

Piazzolla’s music burst from the crossroads of classical music, tango and jazz. “I was asked to play in a band outside of the Conservatory with some freelance musicians. It was the Romance del Diablo. I thought, “’God, that is such a gorgeous tune’.”

Piazzolla’s Romance del Diablo sways, rises, and falls with a tone so fragile the entire piece feels like a single hesitant moment that balances on a decision that carries the weight of the world. “I had an organist position in Paris for a year and there I was able to access a lot more of Piazzolla’s sheet music and recordings,” says James. “I was let into his world.” In Paris, Piazzolla was trying to rediscover who he was after abandoning the tango and the bandoneon, in pursuit of the “serious” classical music he had fallen for: Bartók, Ravel, Stravinsky and Bach.

While studying under Nadia Boulanger at the Fontainebleau Conservatory, he would develop counterpoint, in which multiple musical lines are harmonically interdependent yet independent in rhythm, a motif of his later compositions. While struggling to see himself in the orthodoxy of classical music, one evening Piazzolla played Boulanger his tango piece Triunfal on the piano, and she told him, this is Ástor Piazzolla. He was a man of tango.

From that moment on, Piazzolla began to revolutionise the Argentinian tango by introducing new instruments such as the saxophone and electric guitar, and innovative forms of harmonic and melodic structure into the traditional tango ensemble. In compositions such as Vuelvo al sur, the temperature of the music offered the dancers an opportunity to incorporate slower and larger moves. The old Argentine proverb, "Everything changes except the tango," was sliding into irrelevance.

For James, Piazzolla’s lessons from Boulanger shifted the course of tango. “She was saying, you have to work with your own voice,” he says. “That's going to be your future. You have got to use everything else that you learn about. But don't turn your back on what's really you.” Piazzolla became the most important composer of Nuevo Tango, a revision that charged tango with the elements of his passion; the melting pot of Greenwich village, where jazz crosses over the orchestra, and how the reverb in a bordello might ring out in a concert hall. “He famously said, ‘My music smells of tango.’ He never said that his music was tango,” quips James.

As James became increasingly allured by Piazzolla, he was presented with an opportunity to trace the ghosts of Piazzolla’s sound when he was invited to play lead accordion in Piazzolla’s original band at the Edinburgh Festival. “We had Horacio Malvicino who was a jazz guitarist and probably Piazzolla’s closest friend. We had Hector Console who was his double bass player. And Fernando [Suárez-Paz] as well,” says James. “I probably learned more on [Piazzolla’s] concepts in those rehearsals than any other time because there I was getting first hand information about how Piazzolla worked, what was said about music and the mannerisms of who they are as people.”

In an interview with the BBC, Malvicino said of those rehearsals, “Playing for Ástor was something very special and when he died I always think that he is sometimes with us and sometimes not with us. The first time I talked to James, [Piazzolla] was not here, he was upstairs. But the second time, he was here. And we played different, and everything was so warm and wonderful.” “In Piazzolla’s music there is a form of improvisation that is built into the music,” says James. “You can very quickly learn how far you can go, how you can ornament, what they did in each concert, and what the conversations were about.” James and Piazzolla’s band were trying to come together and articulate Piazzolla’s emotional language. “And there was a quiet nod. If there was that groove going on in an emotionally charged thing. You could see on their faces, they were pleased, they were satisfied. And I thought, this is in the spirit of the music.

The spirit of the music can be traced back to those slums where hope could be heard in a rhythm and freedom could be experienced through dance. “For them, making music’s wonderful and just as wonderful as going out to the restaurant afterwards, talking together, and eating together. It’s a part of their social makeup.”

Piazzolla’s Libertango, which James will perform with the ACO for these concerts, merges the words liberty and tango to mark Piazzolla’s transition from tango to nuevo tango. The shift resulted in death threats – he was even shot at by tango extremists. It was music with meaning – and for Piazzolla, a man who described himself as both Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, meaning can’t be constrained. In a live recording for a Swiss television program, Piazzolla raises his knee onto a box, lights from above cast long shadows down his face, and with the bandoneon in his hands, he stretches open sounds that distill the politics, places and people that shape him.

Watch James Crabb & the ACO performing 'Libertango'

“The accordion can be a very soloistic instrument where you practise a lot on your own and you can perform on your own because it’s like a little portable orchestra the way you use it,” says James. “All the feelings which come out in a lot of the music, you know, you basically play the way you are.” While traversing the tense, sensual and rocky mood of nuevo tango, tangled in Piazzolla’s patterns, James was able to play the way he is. “One of the main attributes of all my teachers was that I was never spoon-fed. So I had to work out myself, why things happen the way they happen.”

For Piazzolla it was on a piano stool at the Fontainebleau Conservatory beneath the gaze of Nadia Boulanger. For James, it was during rehearsals with Hector Malvicino, playing Milonga del Angel, when they could feel Piazzolla in the room.

Click here to buy tickets and learn more about ACO 2022: Piazzolla today.