He was the boy who adored Beethoven – aping the great man’s bold gestures and crashing climaxes in the original works he was chalking up at pace – until he turned to Mozart, attracted to his transparency and control. He was the young man who, during the final years of World War II and hard at work on his first opera, sat in opera performances presented by Sadler’s Wells, punchdrunk on Mozart’s wit, stagecraft and humanity.

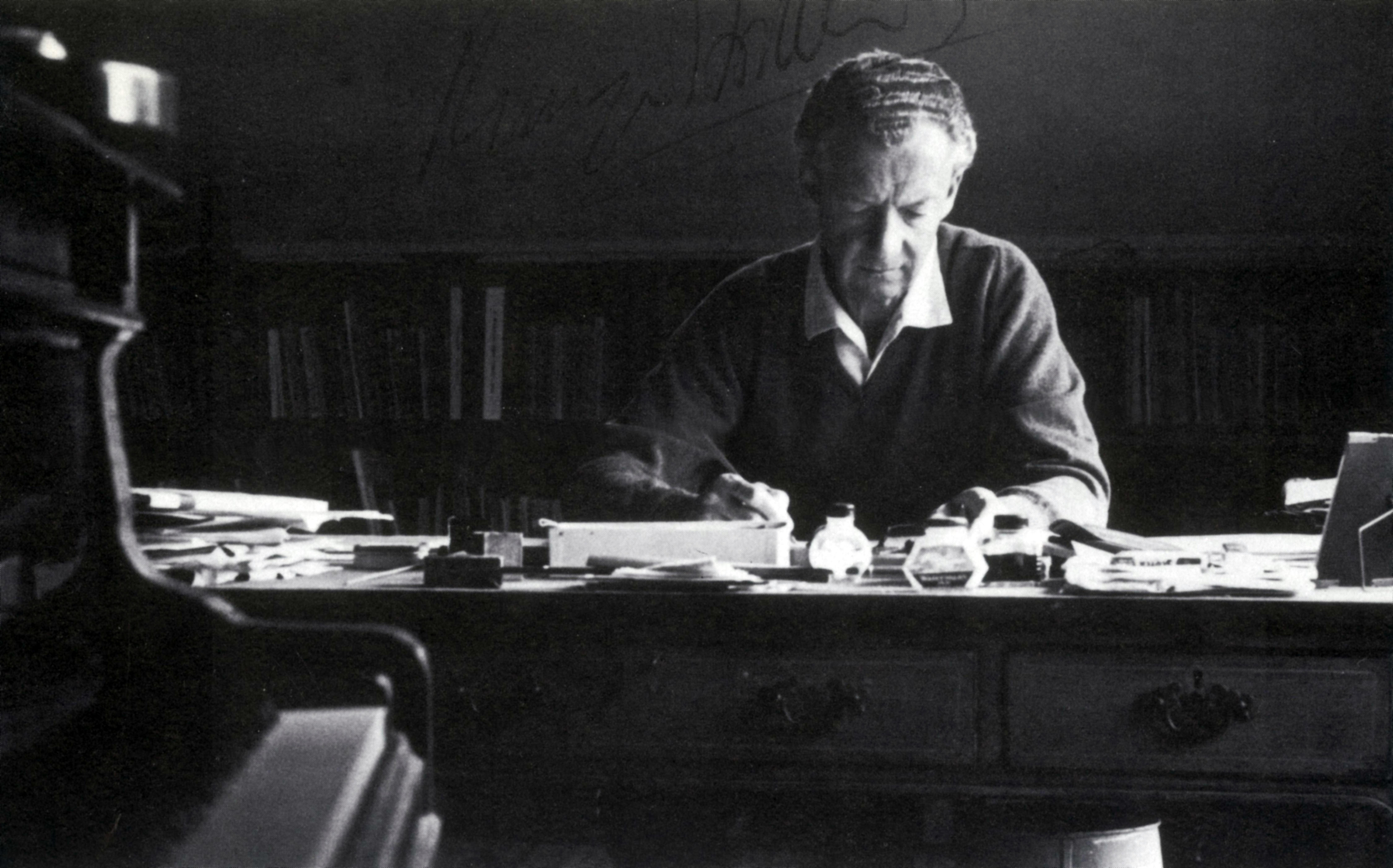

And he was the pre-eminent English composer who, in the magnificent concert hall he had just fashioned from the hulk of an old Suffolk maltings, perched alongside Sviatoslav Richter to play Mozart’s Sonata for Two Pianos, K.448 – a performance that crackled with adrenalin, insight and intensity – the scanty rehearsal time assuaged by the two men’s astonishing musicality.

When asked about his musical villains, Benjamin Britten would respond with weary regret and no little wit (“It’s not bad Brahms I mind, it’s good Brahms I can’t stand”). His heroes – Schubert, Bridge, Mahler, Purcell – received gentle reverence. Yet Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart was in a category of his own – an eternal spiritual presence in Britten’s life and music, a brilliant lodestar never occluded by fast-changing tastes and trends as the young composer journeyed from prodigy to elder statesman.

Without Mozart, it is difficult to see how Britten could have transformed the post-war operatic culture in his homeland as fundamentally as he did. Britten considered Puccini a good opera composer – though not a good composer – for the simple reason that he knew how long it took a person to cross the room.

Yet Mozart taught him something altogether more profound: the moral significance of the characters he put on stage and the importance of their lives and stories for all time. When he articulated these thoughts, Britten was thinking of the character of Figaro, of his relationships with the Countess and Susanna. Yet even then Britten was dimly aware that Billy Budd, the opera he had composed nine years earlier and was now revising – a process that prompted this neat train of thought – could eventually assume a similar mantle.

Long before he arrived at this position, though, there were demons to exorcise, not all of them dispatched in early 1928 when he composed his Elegy (the manuscript specifying 68 strings!). This was the year of his Quatre chansons françaises: those deft, exquisite miniatures, perfumed by Debussy, Ravel and Wagner, composed a few weeks before the 14-year-old commenced as a boarder at W. H. Auden’s old school, Gresham’s in Norfolk.

“So you are the little boy who likes Stravinsky!”, the music master greeted him – ominously, so Britten thought. This heady perfume would soon be replaced by a more original scent, though the four songs presaged the clarity and pared-down textures of Britten’s late works, composed with such urgency as his clackety heart gave up on him.

And for a short while, before they were replaced by others, these scents managed to overpower the Elgarian strains evident in the Elegy, no matter that mere months separated the two works. The broad stylistic experimentation and gradual emergence of his own voice in 1928 came about because Britten had begun lessons with Frank Bridge the previous year, his mentor gamely working through the satchel full of new works his pupil brought to each session. Bridge taught him craft, and discipline too, but most importantly he encouraged his young pupil to dive into the deep, rich pool of European Modernism, a pool Britten would otherwise have approached with trepidation.

When Britten began working with Bridge, he was still four years from writing his opus one (the Sinfonietta, lightly flecked with the colours of Schoenberg’s Kammersymphonie, an unimaginable influence pre-Bridge), and there were high and low mountains to climb before he got there. But so too were there constants: his schoolboy diary charts his deep love of Mozart, a grand passion illuminated by a magical sequence of orchestral scores, concerts, radio broadcast, gramophone recordings, piano music, and more besides.

In November 1931 he attended a performance of Mozart’s Sinfonia Concertante, with Albert Sammons and Lionel Tertis as soloists (the latter a disappointment, he thought), the whole thing way too sloppy under his bête noire Adrian Boult. And at Christmas his family gave him miniature scores of Petrushka and the Sinfonia Concertante, the latter now a favourite work.

Perhaps inevitably, early the following year he set up his stall on Mozart’s patch. With his Christmas gift close to hand, he composed a concerto for violin and viola (published 70 years later as his Double Concerto), with which he was quickly dissatisfied, but nevertheless hints at the absolute breakout work to come, his Violin Concerto of 1939.

There is a lyrical tenderness to the solo writing that is indebted to Mozart, a quality that would soon characterise much of his work. Works such as the Double Concerto – less so the Elegy – did one more thing: they acted as a time capsule, containing compositional ideas that had been fully worked out before being discarded, reluctantly, and which Britten occasionally dug up for inspiration. He repurposed a melody in the finale of the Double Concerto in Billy Budd, and the movement itself is his first successful use of moto perpetuo, a technique he’d return to so successfully in many works, including the astounding Cello Sonata (1961), his third cello suite (1971), and the Variations on a theme of Frank Bridge (1937) – the year in which his music began to get really interesting.

Does any of this apply to the Mozart of the Divertimento (1772)? He composed the piece as 15-year-old – Britten wrote his Elegy at a similar age – at home in Salzburg, fresh from two trips to Italy in the company of his father. It’s not strictly a divertimento, which tended to be more ragtag in shape than the cohesive symphonic design of this early work.

The Mozart scholar Alfred Einstein once speculated that perhaps the piece was in fact the skeleton of a symphony, should a third trip to Italy require such a work; Mozart would then merely need to punctuate it with winds and brass (the key of D would facilitate such manoeuvres). And Mozart himself labelled the work a “Salzburg Symphony”, no matter the designation under which it was published. Yet even this looseness with genre at such an early age would pay enormous dividends in mature works. As Britten would do 150 years later in London, Mozart transformed the operatic culture of his adopted city, Vienna, precisely because he knew so well the rules he broke so freely, an iconoclast to the core.

There were tributes, too, in his music, some acknowledged, others implicit. Here the young Mozart was like the young Britten, absorbing everything he could – from ecclesiastical music to antiquarian scores – and letting it colour his own imagination and output. Haydn was merely his most obvious hero and cheerleader, the younger composer dedicating a series of six string quartets to the older, prompting Haydn’s famous observation to Mozart’s father: “Before God and as an honest man, your son is the greatest composer known to me in person or by name...”.

Prodigious talent, early recognition, mentorship, self-belief, a dash of humility: it’s a potent mix. It doesn’t always end the way it should: for every Mendelssohn there’s a Hummel, for every Mozart there’s a sister – in his case the prodigious Maria Anna. Yet planets do sometimes align, and humanity is changed forever. The resulting hat-tips between generations are heartfelt, often gorgeous. The six quartets Mozart dedicated to Haydn redefined the genre. And the score Britten dedicated to his great teacher and mentor, the Variations on a Theme of Frank Bridge, was as much an expression of the music he was leaving behind – though he would never lose his fondness for variation form – as it was a stunning example of the music he would now start composing with such confidence and consistency.

The two men had one more thing in common, and not simply that Britten’s variations were premiered in Salzburg a matter of three months after the conductor Boyd Neel commissioned them. They both shared Vienna, an antidote to the provincialism each identified in his hometown: a glamorous, daring character in her own right. It was the city Mozart changed, no matter the struggle, and the place that intensified Britten’s steely vision when, upon leaving college, he discovered there a level of music-making so foreign to him, putting fire in his belly for the battles to come.

In April 1945, as Soviet troops captured Vienna from the Germans, Britten recorded a short BBC radio broadcast in which he reflected on the significance of the city in European cultural imagination. It was the actual or spiritual home of Mozart, Schubert, Gluck, Haydn, Mahler, Berg and Schoenberg, its heritage and legacy too important to be lost as mere spoils of peace. It was a rallying cry for the survival and recovery of both city and culture, a repayment of a debt that had begun accruing when Britten’s “childish fingers stumbled through the sonatas of Mozart”, the small boy unaware of the lasting significance of these early fumbles.

Tickets are on sale for ACO's Mozart Sinfonia Concertante, featuring Richard Tognetti and Stefanie Farrands as soloists. Click here to book now.