Crossing the shaky suspension bridge, I watched a rivulet of water run down Richard Tognetti’s violin case. At a metal clasp it braided, as rivers do, before confluencing below the buckle. Then into freefall, a tiny cascade dropping five metres to the Snowy River below.

That rain was falling late on a dull September afternoon as Tognetti and I trudged into the gloom. We had plans for a few days’ backcountry skiing, hopes for an improvement in the weather and thoughts of high jinks with a violin.

We woke the following morning to blue skies and, after brewing coffee for need and porridge for necessity, skied away from our camp and climbed onto the main ridge of the Snowy Mountains.

After skiing a couple of glorious runs on sun-softened snow, Richard swapped ski poles for the violin. Then, as a celebration of mountains and rivers everywhere, in surely one of the finest venues he had ever played, he took off, linking turn after tune after turn.

The rainwater that had fallen from the violin case the day before, dropped into the only section of the Snowy River still running free, a meagre stretch below the slopes of Mount Kosciuszko. How long, I wondered, would it take that water to travel 400 kilometres to the sea at Marlo? Guthega Dam would hold those molecules first, then Island Bend.

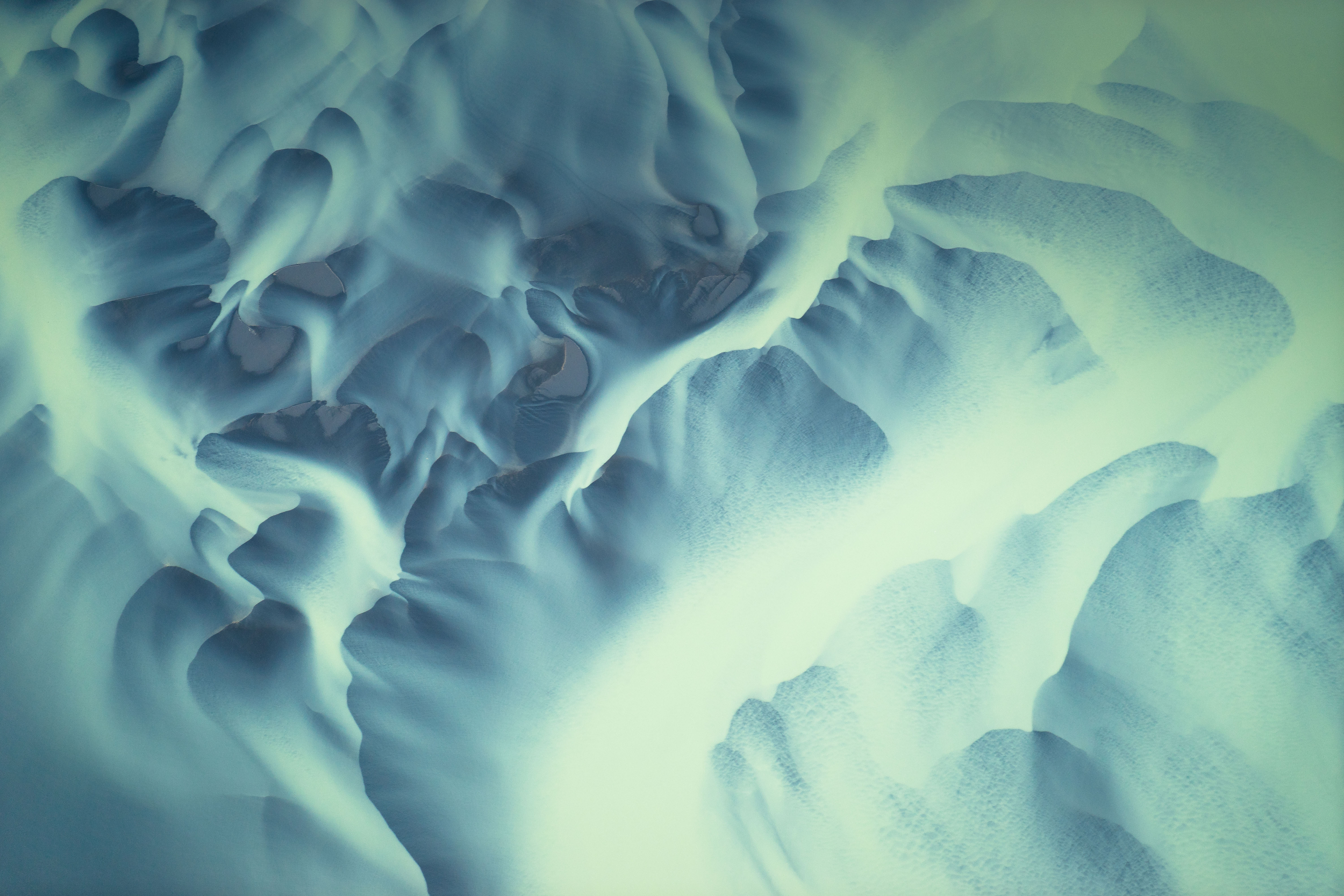

If they did escape beyond those walls, they might bounce down into the expanse of Lake Jindabyne. Here they could be held for months or years before gaining freedom through a release into the Snowy below Jindabyne Dam. The ingenuity of the Snowy Scheme meant even that was no guarantee. Tunnels and pumps might take that water far from its natural course, under and across the mountains and away into arid lands to nourish cotton, rice or almonds.

Just two months later, in the warmth of late spring, I paddled the Snowy River below that final dam in Jindabyne, astounded by the terrain. Deep in the gorges, one rapid catapulted me out of my craft. I swam, pinballing off rocks that hurt me despite the cushioning of the water piling onto the smooth, waterworn, granite boulders.

For decades, a miserable one per cent of natural flow was allowed to dribble down this artery. The past 20 years have seen this increase towards a fifth, thanks to a huge campaign in the ’90s to save the Snowy. But water that flows from a dam is not the same as water that flows naturally. It is often colder, taken from the bottom of a pondage and lower in nutrients. Such water impacts the natural biorhythms of the waterway below.

At camp, a pair of bee-eaters entertained us all afternoon, flitting about the branches of a single, dead gum. Platypus popped up for a look from the pool below our tents and a flightless emu looked up longingly at those that could. A pair of dingos looked on nonchalantly. Had the water from Richard’s violin case yet arrived in this part of the Snowy, I wondered? Or was it still making its way uncertainly down the river?

ACO 2024: River Live in Concert

Touring 1 - 16 Feb, to Newcastle, Melbourne, Canberra, Sydney, Brisbane and Perth.